Forty years ago I began to collect data on fishing in the cold. Not that I ever minded cold weather, but somewhere there must be a lower limit where good sense prevails, if a person has good sense. So I began to wonder where to draw that horizontal line across my yard thermometer.

The first clue came to me on a February trout-fishing trip in the mountains of Virginia. When we arrived at streamside, ice fringed the banks and the thermometer would have said sixteen degrees, had it not been shivering too hard to do more than stutter.

This trip took place in my ultra-light days. I had a little fiberglass twig of a rod outfitted with four-pound-test mono. Looking back, the spinning reel I’d improvised onto the rod made it heavy in the handle, but I balanced it by holding the reel seat in my hand.

The stream we picked tumbled from the bottom of a deep lake with water leaving the dam at about forty-five degrees, which helped keep the trout active through the winter. Knowing the fish were warmer than I was brought no consolation.

Not an hour into the morning, I cast into an overhanging alder across the river. Giving my rod a quick jerk, I heard a snap closer than I’d expected and found myself still hung but my one-piece rod now had two pieces. Frozen fiberglass apparently has less forgiveness than warm fiberglass.

Snapping a rod in half does have a warming effect, though it’s not a comforting sort of warmth.

Popping the line by hand, I reeled in and headed back to the car to salvage the morning. As I walked the trail by the stream, a flash caught my eye. At the bottom of a deep pool, a bronze flash repeated, obviously the tipping belly of a big brown.

Without thinking, something I apparently do frequently, I retied with an inviting offer, held the broken rod tip in my right hand as if leading an orchestra, and flipped a cast. My line drifted through the pool and stopped where the fish was. Holding the two pieces together now with my right hand, the reel handle in my left and the rod butt wedged between my wading belt and my belly, I jerked and met resistance.

At that precise moment, I had an inkling that perhaps this was a mismatched fight, something along the lines of Ali boxing Elmer Fudd. But without a referee, all I could do was wait to see if the fish had any mercy in him. At least I had a prime seat for the event.

Slowly, as if annoyed, a brown that would have qualified for The Biggest Loser rose to the surface. His curled lower lip protruded in a snarl. Methodically, he began bulldogging his head as if throwing body punches to my ribs. I watched helplessly as he raked those sharp teeth across my four-pound mono until it lay limp on the surface.

I concluded with the observation that sixteen degrees may be too cold for fiberglass, but it is not too cold to fish. Perhaps, however, there were other variables to consider.

A few years later, I found myself gathering data in the Rockies. I’d been watching ice fishermen on a Colorado mountain lake and wondered if a person really had to fish through a little hole in the ice. With a little effort, I found my answer.

Where the main stream flowed into the lake the turbulence prevented a total freeze. At that seam, a person could drift a line up under the ice. I never checked a thermometer, but with the lake frozen over and almost four feet of powder back in the woods (judging by the snow line on my chest), I guessed the temperature might be in single digits.

Fumbling with rod, line and rag wool mittens, I surmised I might not waste much time on midwinter fishing in the Rockies. To my surprise, however, I soon learned that rainbows do feed in such conditions and those who are hungry probably line up where the stream dumps in.

The bite was timid, almost as if the fish didn’t want to waste a lot of energy. The ensuing fight, however, was spirited and eventually I slid a three-pound rainbow up onto the snow. Being a conservationist but not a preservationist, I decided to hold this one for dinner. I stuck my arm into the snow, poked the trout in head-first, and covered him with just his tail protruding.

Warmed with the excitement of the moment, I must have kept fishing for a while. By the time I retrieved my fish, I had to chip him out. Holding him by the tail, he was stiff as a fish-cicle and only after thawing it back at the cabin was I able to filet two shrimp-pink slabs off for dinner.

Once again, cold as it was, it was not too cold to fish, only too cold to clean fish.

Since then, I’ve fished northern latitudes and higher elevations collecting more cold-weather data. I’ve fished rivers with chunks of ice floating in them in between sections totally frozen over. Countless times the eyes on my fly rod have iced over and had to be chipped out every few minutes. I’ve mumbled multiple epithets regarding the inventor of fingerless gloves. And I own at least a dozen pair of wool socks, still searching for some bold enough to defend my old toes from the cold.

Rods have improved and I’ve not broken one from the cold in several decades. I rarely keep trout anymore, so I’ve had no need to thaw fish frozen in snow banks. Only recently have I collected any data that would suggest it can be too cold to fish.

Over the Christmas holidays, I started suffering from cabin fever and needed to wet a few flies. A snow storm had dumped six inches of fresh snow in the North Carolina mountains, so I knew the river I had in mind would be peaceful and scenic. Or, in other words, what fool besides me would pick such a day to fish?

My four-wheel-drive pickup made the first set of tracks down the turn-off to the section I planned to fish. My waders left the only set of footprints in the snow from the pull-off to the stream. Not even critters were moving much, the only evidence being a few bird tracks where they hopped in search of food or a warmer roost.

The water gurgled low and clear. I tied on a pre-rigged stonefly with a pheasant-tail dropper, a combination that normally produces in the winter. A glob of snow plopped into the pool in front of me, shaken loose by the breeze that was picking up.

As the storm had passed and the clouds cleared, the temperature fell steadily. The wind whispered through the hemlock tops and the trees groaned, as they were too cold to sway. I groaned with them.

After a couple of fishless hours, I slipped cold fingers into an inside pocket and pulled out a chunk of peppered beef jerky. Short of a Saint Bernard with a brandy keg under its neck, I’ll take spicy jerky to get my blood flowing. Because at that moment, I’d lost all feeling in my feet.

Thinking this a relevant observation, I looked at the low stream flow, all the snow that wasn’t melting, and I knew this was cold water, probably just far enough above freezing to flow. Not even that warm on the edges where pockets lay beneath a crust of ice.

I thought back forty years to that February in Virginia when it had been sixteen degrees in the air but remembered the water had been in the forties. Then, in Colorado, when my slab-sided rainbow had frozen on the bank, he’d obviously been just fine under the ice. That’s when it became clear that for all these decades I’d been asking the wrong question.

The question isn’t, “When is it too cold for me to fish?” The real question is, “When is it too cold for the fish?”

Knee-deep in a North Carolina trout stream, with no feeling in my toes, snow glistening in the hemlocks, and not a trout to my credit, that last question I could answer at least for this day. It’s too cold to fish when the fish say so.

Awarded First Place in the Southeastern Outdoor Press Association Excellence

in Craft Competition

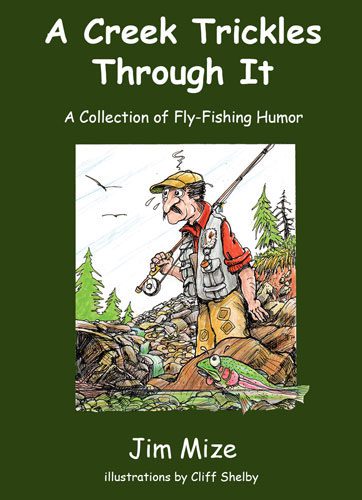

Award-winning author, Jim Mize, has written a humorous book specifically for fly fishermen. Titled, A Creek Trickles Through It, this collection delves into such topics as carnivorous trees, persnickety trout, and the dangers of fly-tying. This book was awarded first place in the Southeastern Outdoor Press Association’s Excellence in Craft competition. Whether you are an arm-chair fisherman or one with well-earned leaky waders, it will be a welcome addition to your fishing library.

Jim has received over eighty Excellence-In-Craft awards including one for his first book, The Winter of Our Discount Tent. His articles have appeared in Gray’s Sporting Journal, Fly Fisherman Magazine, Fly Fishing & Tying Journal, as well as many conservation publications. You may order copies through Amazon or get autographed copies from his website at www.acreektricklesthroughit.com

“Too Cold to Fish” is an excerpt from Jim’s award-winning book, A Creek Trickles Through It. You can find the book online or order autographed copies from www.acreektricklesthroughit.com. Jim Mize e-mail: Jimmize1@cs.com One-Time Publication rights.