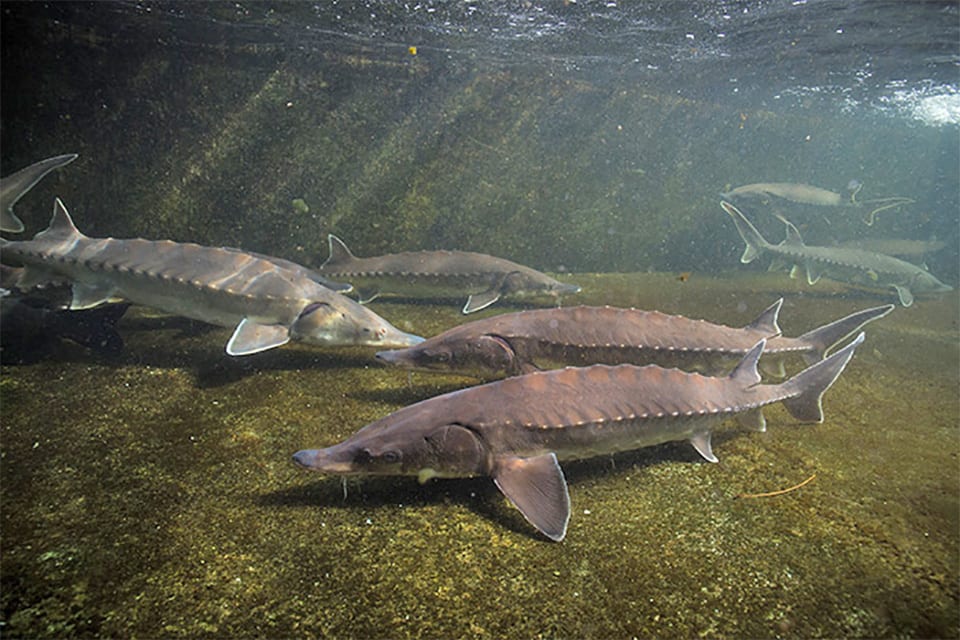

Albert Spells, Virginia Fisheries coordinator for the Service, didn’t believe Atlantic sturgeon were gone from the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Photo by USFWS

Many believed the Atlantic sturgeon were gone from the Chesapeake Bay watershed. They hadn’t been sighted in rivers that fed the bay for decades. But a few experts, including Albert Spells, Virginia Fisheries coordinator for the Service, thought otherwise, and they worked to recover this fish, engaging concerned citizens, scientists, commercial watermen, state and federal agencies, nonprofit groups, educators, graduate students and volunteers.

Conservation, however, takes commitment to playing the long game, especially when the species you wish to restore is long-lived and doesn’t reproduce until it’s at least 10 years old. But, winning is possible with great partners, a lot of volunteers and dedication to solving unknowns.

Atlantic sturgeon are coming back in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Photo by Ryan Haggerty/USFWS

Atlantic sturgeon, one of the oldest and largest fish on earth (growing upward of 14 feet long and weighing more than 800 pounds) were once found in huge numbers along the Atlantic Coast and coastal rivers from Canada to Florida. They were an important food for indigenous peoples along the coast and likely saved Jamestown colonists from starvation.

During the great “Caviar Rush” or “Black Gold Rush,” in the late 1800s, Atlantic sturgeon became a highly prized fishery. Harvest peaked at 700,000 pounds in Chesapeake Bay waters alone in the late 1890s with a total of 7 million pounds in landings from all East Coast states. By 1989, a mere 400 pounds were reported in all of the United States, with few records of them returning to the Chesapeake Bay. Within a hundred years, a species that had lived on the planet for hundreds of millions of years had been overfished.

But Spells and Jim Owen at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) didn’t think it was gone. “You know,” Owen said to Spells one day “they’re catching sturgeon on the James and the York [rivers], but the watermen aren’t gonna tell you about it unless you put something in it for them.” Spells agreed and began cobbling together pots of money from the Service, Virginia, Maryland and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) to implement a reward program, “so we could verify if sturgeon were returning to our rivers and tag them,” Spells says. “In 1997, a $100 reward (later $50) administered by VIMS was offered to commercial watermen who caught an Atlantic sturgeon in Virginia and kept them until the Service could tag and release the sturgeon back into the rivers. In less than a year, they had caught 303 fish, including 2-and 3-year-old fish,” he adds.

Young Atlantic sturgeon. Photo by Matt Balazik

“We learned that there was a larger population of sturgeon using Virginia waters than previously realized, and we had evidence of successful spawning. Our efforts encouraged others to start looking for sturgeon in the bay.”

The reward program in Virginia ended after two years, but the coast-wide tagging program that began in 1992 with more than 31 participating agencies from Maine to Georgia continues. Coordinated through the Service’s Maryland Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office, the program allows the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission to delineate migratory patterns and learn where sturgeon may be spawning successfully.

Besides overfishing, other factors were impacting the sturgeon’s survival — pollution, loss of spawning grounds due to heavy siltation, bycatch (fish caught in fishing gear targeting other commercial species) and ship-strikes.

Atlantic sturgeon breaching in the James River. Photo by Don West

In 1998, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission called for a moratorium on sturgeon fishing, and all 15 states complied. The goal was to protect sturgeon for 20 years, allowing them to reproduce and their populations to grow. Then in 2012, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries listed four populations of Atlantic sturgeon as endangered, one of which was the Chesapeake Bay.

“Our coast-wide tagging program helped us learn where sturgeon go, but we still weren’t finding evidence of spawning or young of year fish,” fish born in that year, says Spells. Finding these super young, less than a year-old fish is significant because it indicates where the adults have been spawning.

The Service’s Albert Spells (left) and Matt Balazik, with the Engineer Research and Development Center for the Army Corps of Engineers, collect sturgeon.

Photo by Charles Frederickson/James River Association

Matt Balazik, biologist with the Engineer Research and Development Center for the Army Corps of Engineers, and his team with the Virginia Commonwealth University’s (VCU) Rice Rivers Center, collected 153 young of year Atlantic sturgeon in the James last fall. “This was the first finding of young of year that anyone can recall since…March 2004,” Balazik says. Before that, “the last time we had evidence of sturgeon spawning in the James was 1979,” he says.

“Through Matt’s research, we learned a lot” Spells says. “For example, we discovered that the sturgeon spawn in the fall, when everyone thought they only spawned in spring.”

“There’s no way, however, we would have learned all that we know now if not for the many partners advocating and working to save this species.”

Whether it was a researcher developing fishing gear to reduce bycatch but keep striped bass fishing effective, partners building spawning reefs or finding better sturgeon sampling techniques, Spells says, “It took universities (VIMS, VCU, University of Maryland), NGOs (CBF, James River Association), the states, Fish and Wildlife Service, NOAA, Virginia Sea Grant, and many volunteers working together to find and recover Atlantic sturgeon.”

Atlantic sturgeon may have been pulled from the brink, but they aren’t recovered yet. It may take decades for them to rebuild their populations. But through science, environmental regulations, improvements to spawning grounds and outreach, we are saving this amazing prehistoric fish, just as it once saved Jamestown.

CATHERINE GATENBY, Fish and Aquatic Conservation, Northeast Region