By Terry Gibson:

Since early childhood in the 1970s, I’ve attended West Palm Beach Fishing Club events. Each time I walked into the club house, I couldn’t help but stare at the two giant bluefin mounted on the walls, and think how grossly unfair it is that anglers my generation and younger would probably never get a reasonable chance at catching such a majestic fish.

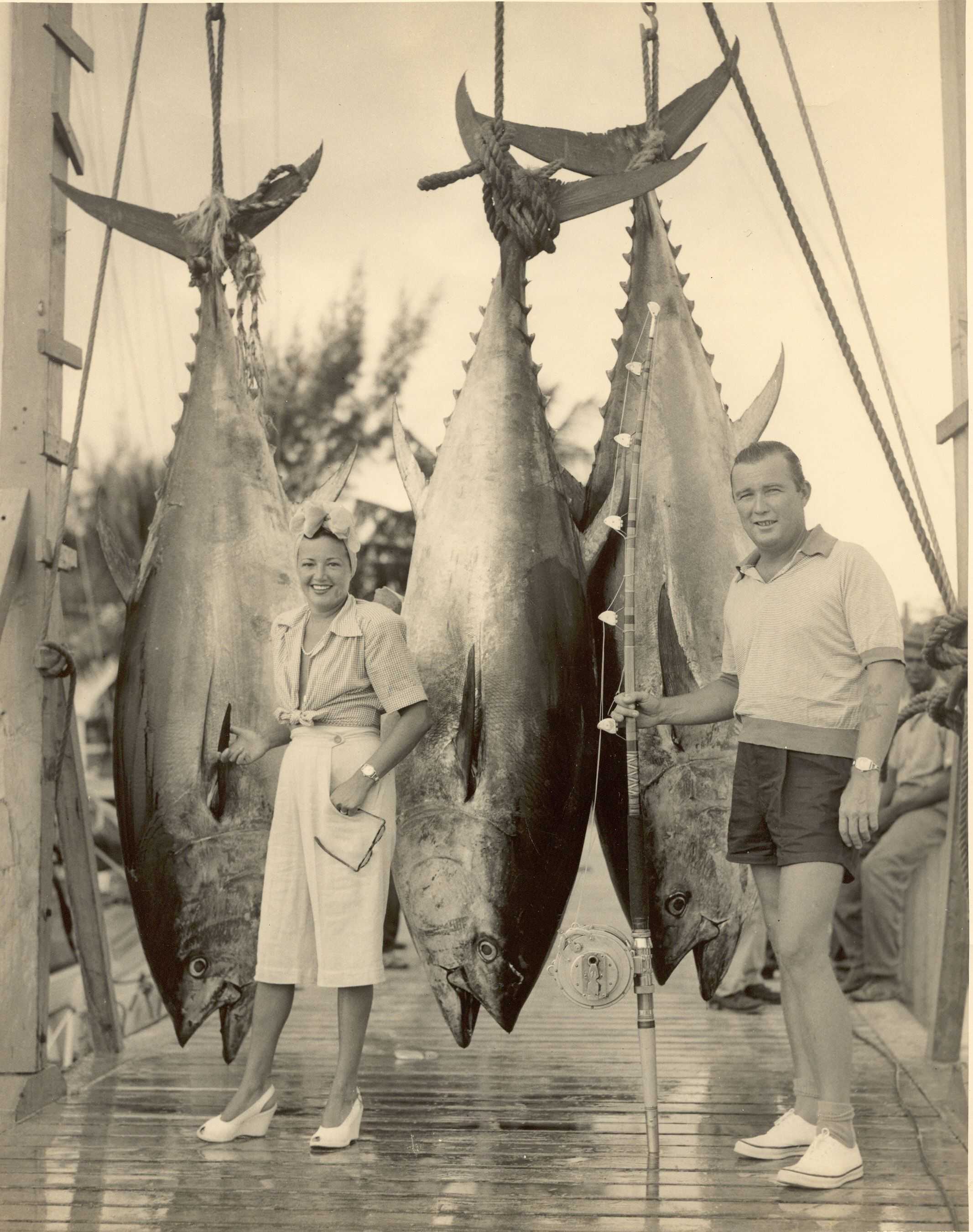

Here on Florida’s southern Atlantic coast, it’s just a few hours run to Tuna Alley, off Cat Cay, The Bahamas. That legendary bluefin sight fishery spawned many tackle advancements, including the development of the “tuna tower,” forever changing the way we think a sportfisher should look. But by the mid 1980s, the last of the bluefin tournaments in Cat Cay and Bimini folded. The fish were virtually gone, victims of rampant overfishing.

In the summer of 2009, my fishing buddy Tom Wheatley asked for help gathering the recreational fishing community’s support for restoring the Western Atlantic bluefin population. Tom, already a veteran fish conservation campaigner, had gone to work for the Pew Charitable Trusts, managing a campaign to end surface long-lining in the Gulf of Mexico, where the western or “American” population of Atlantic bluefin spawn.

Pew wanted to put together a broad-based coalition to resolve this longstanding issue of longlines killing the breeder bluefins in the waters where for countless millennia they’ve returned each year to reproduce. Since the early 1980s, marine scientists have increasingly encouraged a management emphasis on protecting fish when they spawn and protecting the places where they spawn. The idea is pretty simple: If you protect the essential habitats and spawning fish then you will likely enjoy larger populations.

Commercial longliners have not been allowed to deliberately target bluefin in the Gulf, or elsewhere in U.S. waters for that matter. But they have used longlines to fish for yellowfin tuna and swordfish in the bluefin feeding and spawning areas. Baiting hundreds of hooks on miles of line is an indiscriminant way to fish, and the bycaught bluefin don’t often survive if released. There are also financial incentives for longliners to land bluefin as “bycatch.” So it was clear that if we want to see bluefin return to something of their former glory, then we needed to get the longlines out of the water when and where the fish are most vulnerable.

The campaign took almost five years to succeed, and during those four years it had “curveballs” as sharp as the Deepwater Horizon disaster thrown at it, which made NOAA understandably loathe to do anything to impact Gulf fishing of any type. But thanks to a non-traditional partnership including recreational fishing/conservation groups, a great deal was struck. The Highly Migratory Species Division (HMS) of the National Oceanographic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) must be praised for its exhausting analyses and extensive outreach. Recreational fishing/conservation groups, especially the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) and Russell Nelson, RIP, formerly with CCA and The Billfish Foundation, deserve much appreciation, as do independent conservation groups including the Pew Charitable Trusts, Earth Justice and Natural Resources Defense Council.

In January, the Highly Migratory Species Division (HMS) of the National Oceanographic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released Amendment 7. As of 2015, longlining is prohibited seasonally in three new areas covering about 27,000 square miles, including 5,500 square miles off of North Carolina—a popular feeding area for bluefin—and 21,500 miles of bluefin spawning areas in the Gulf of Mexico.

In addition to these time and area-based regulations on longline fishing gear, the agency will implement a new national annual cap on the total amount of incidental bluefin catch. Once the bluefin cap is reached, longline fishing must stop. Longline fishing boats also must comply with new reporting requirements, including having video cameras on board to record what’s being caught and discarded and providing real-time bluefin catch and fishing effort data to NOAA Fisheries while on the water.

It’s a great story about what can be achieved when groups and agencies that don’t always see eye to eye agree to work together where there is a clear problem. Bluefin experts think that depending upon the impacts of the Deepwater Horizon spill and other factors, we may see a noticeable increase in western Atlantic bluefin populations within a few years. The species matures fairly rapidly and is extremely fertile. It’s suspected but not known for certain whether the fish that glide over The Bahamas Bank come from spawning in the Gulf, but thanks to the Merritt family and Costa Del Mar’s Bluefin on the Line campaign, we will be getting more information from satellite tags. Costa will hold an annual tag-and-release tournament out of Cat Cay. Here’s to the hopeful return of the western Atlantic’s most iconic fishery.

Atlantic Bluefin Facts

- About half the fish caught off the Mid-Atlantic and New England migrate clear across the Atlantic and back. These fish were hatched in the Mediterranean Sea.

- The other Atlantic bluefin population—the so-called “American” population—spawns during the spring in the gyres of the Gulf of Mexico, the only verified spawning ground for the species in the western Atlantic. They swim as far north as the Canadian waters off Labrador and Newfoundland.

- The two populations don’t often spawn together. In fact, the percentage of fish with “Med” and “American” genes is on par with the tiny amount of mixing that occurs between salmon runs in different Pacific rivers.