By Michael Douglas as told by John W. Wasik. The story was featured in “The Cumberland Times,” October 27, 1963, titled “I BATTLED A MONSTER FISH FOR 33 HOURS.”

I had been battling the monster fish for 24 hours. My arms ached and my legs felt as if they had doubled in weight. Maybe I was half-asleep, too. At any rate, the huge fish suddenly veered out toward the Atlantic Ocean. The terrific tug nearly toppled me into the churning surf which dashed against the pilings of the pier.

I set the drag on my reel and pulled until my homemade cane pole was bent like a horseshoe, and my back was ready to break. But it was no use. With the force of a bulldozer, the sea brute stole previous yards of line. I knew it was almost over and summoned every ounce of strength left to turn back the fish.

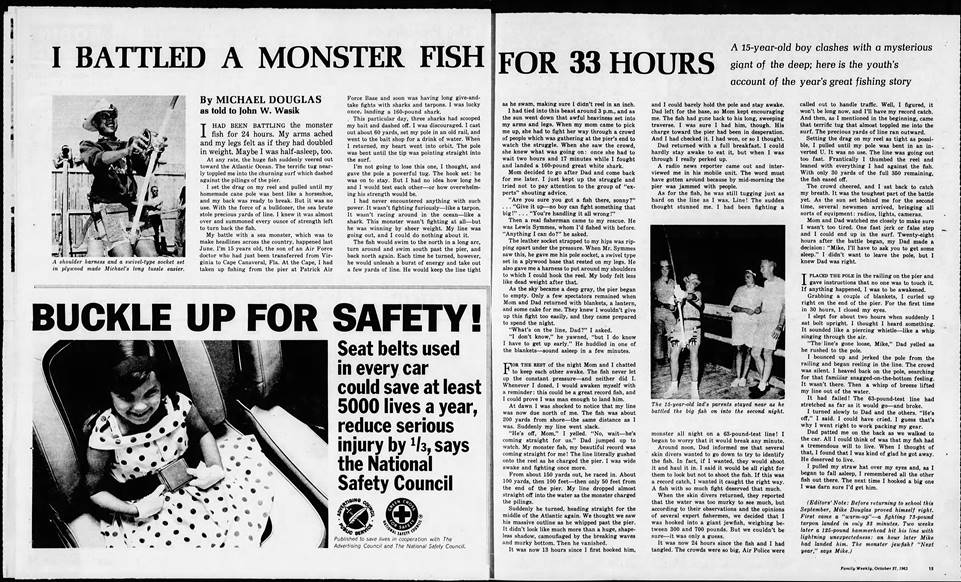

My battle with a sea monster, which was to make headlines across the country, happened last June. I’m 15 years old, the son of an Air Force doctor who had just been transferred from Virginia to Cape Canaveral, Fla. At the Cape, I had taken up fishing from the pier at Patrick Air Force Base and soon was having long give-and-take fights with sharks and tarpon. I was lucky once, landing a 160-pound shark.

This particular day three sharks had scooped my bait and dashed off. I was discouraged. I cast out about 60 yards, set my pole in and old rail, and went to the bait shop for a drink of water. When I returned, my heart went into orbit. The pole was bent until the tip was pointing straight into the surf.

I’m not going to lose this one, I thought, and gave the pole a powerful tug. The hook set: he was on to stay. But I had no idea how long he and I would test each other — or how overwhelming his strength would be.

I had never encountered anything with such power. It wasn’t fighting furiously—like a tarpon. It wasn’t racing around in the ocean—like a shark. This monster wasn’t fighting at all—but he was winning by sheer weight. My line was going out, and I could do thong about it.

The fish would swim to the north in a large arc, turn around and swim south past the pier, and back north again. Each time he turned, however, he would unleash a burst of energy and take out a few yards of line. He would keep the line tight as he swam, making sure I didn’t reel in an inch.

I had tied into this beast around 3:00PM., and as the sun went down that awful heaviness set into my arms and legs. When my mom came to pick me up, she had to fight her way through the crowd of people which was gathering at the pier’s end to watch the struggle. When she saw the crowd, she knew what as going on: once she had to wait two hours and 17 minutes while I fought and landed a 160-pound great white shark.

Mom decided to go after Dad and come back for me later. I just kept up the struggle and tried not to pay attention to the group of “experts” shouting advice.

“Are you sure you got a fish there, sonny?” …“Give it up—no boy can fight something that big!”…“You’re handling it all wrong!”

Then a real fisherman came to my rescue. He was Lewis Symmes, whom I’d fished with before. “Anything I can do?” he asked.

The leather socket strapped to my hips was ripping apart under pressure. When Mr. Symmes saw this, he gave me his pole socket, a swivel type set in plywood base that rested on my legs. He also gave me a harness to put around my shoulders to which I could hook and reel. My body felt less like dead weight after that.

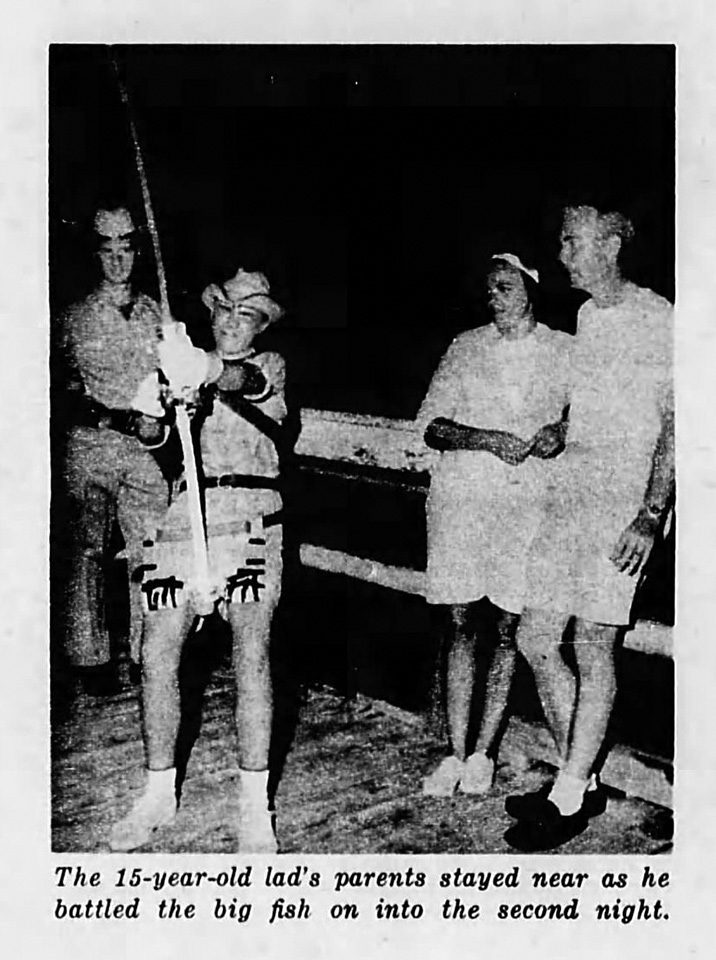

As the sky became a deep gray, the pier began to empty. Only a few spectators remained when Mom and Dad returned with blankets, a lantern and some cake for me. They knew I wouldn’t give up this fight too easily, and they came prepared to spend the night.

“What’s on the line, Dad? I asked. “I don’t know,” he yawned, “but I do know I have to get up early.” He huddled in one of the blankets—sound asleep in a few minutes.

For the rest of the night mom and I chatted to keep each other awake. The fish never let up the constant pressure—and neither did I. Whenever I dozed, I would awaken myself with a reminder: this could be a great record fish, and I could prove I was man enough to land him.

At dawn I was shocked to notice that my line was now due north of me. The fish was about 200 yards from shore— the same distance as I was. Suddenly my line went slack.

“He’s off, Mom,” I yelled. “No, wait—he’s coming straight for us.” Dad jumped up to watch. My monster fish, my beautiful record was coming straight for me! The line literally gushed onto the reel as he charged the pier. I was wide awake and fighting once more.

From about 150 yards out, he raced in. About 100 yards, then 100 feet—then only 50 feet from the end of the pier. My line dropped almost straight off into the water as the monster charged the pilings.

Suddenly he turned, heading straight for the middle of the Atlantic again. We thought we saw his massive outline as he whipped past the pier. It didn’t look like much more than a huge, shapeless shadow, camouflaged by the breaking waves and murky bottom. Then he vanished.

It was now 13 hours since I first hooked him, and I could barely hold the pole and stay awake. Dad left for the base, so Mom kept encouraging me. The fish had gone back to his long, sweeping traverse. I was sure I had him, though. His charge toward the pier had been in desperation. And I had checked it. I had won, or so I thought.

Dad returned with a full breakfast. I could hardly stay awake to eat it, but when I was through I really perked up.

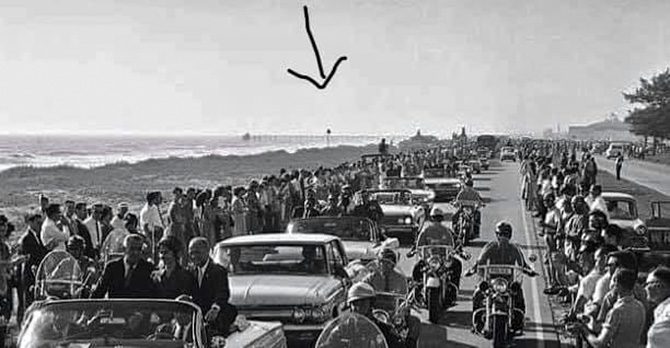

A radio news reporter came out and interviewed me in his mobile unit. The word must have gotten around because by mid-morning the pier was jammed with people.

As for the fish, he was still tugging just as hard on the line as I was. Line! The sudden thought stunned me. I had been fishing a monster all night on a 63-pound test line! I began to worry that it would break any minute.

Around noon, Dad informed me that several skin divers wanted to go down to try to identify the fish. In face, if I wanted they would shoot it and haul it in. I said it would be all right for them to look but not to shoot the fish. If this was a record catch, I wanted it caught the right way. A fish with so much fight deserved that much.

When the skin divers returned, they reported that the water was too murky to see much, but according to their observations and the opinions pdf several expert fisherman, we decided that I was hooked into a giant jewfish, weighing between 300 and 700 pounds. But we couldn’t be sure—it was only a guess.

It was now 24 hours since the fish and I had tangled. The crowds were so big, Air Police were called to handle traffic. Well, I figured, it won’t be long now, and I’ll have my record catch. And then, as I mentioned in the beginning, came that terrific tug that almost toppled me into the surf. The precious yards of line ran outward.

Setting the drag on my reel as tight as possible, I pulled until my pole was bent in an inverted U. It was no use. The line was going out too fast. Frantically I thumbed the reel and leaned with everything I had against the fish. With only 30 yards of the full 350 remaining, the fish eased off.

The crowd cheered, and I sat back to catch my breath. It was the toughest part of the battle yet. As the sun set behind me for the second time, several newsman arrived, bringing all sorts of equipment: radios, lights, cameras.

Mom and Dad watched me closely to make sure I wasn’t too tired. One fast jerk or false step and I could end up in the surf. Twenty-eight hours after the battle began, my Dad made a decision: “Mike, I’ll have to ask you to get some sleep.” I didn’t want to leave the pole, but I knew Dad was right.

I placed the pole in the railing on the pier and gave instructions that no one was to touch it. If anything happened, I was to be awakened.

Grabbing a couple of blankets, I curled up right on the end of the pier. For the first time in 30 hours, I closed my eyes.

I slept for about two hours when suddenly I sat bolt upright. I thought I heard something. It wounded like a piercing whistle—like a whip singing through the air.

“The line’s gone loose, Mike,” Dad yelled as he rushed to the pole.

I bounced up and jerked the pole from the railing and began reeling in the line. The crowd was silent. I heaved back on the pole, searching for that familiar snagged-on-the-bottom feeling. It wasn’t there. Then a whip of breeze lifted my line out of the water.

It had failed! the 63-pound test line had stretched as far as it would go—and broke.

I turned slowly to dad and the others. “He’s off,” I said. I could have cried. I guess that’s why I went right to work packing my gear.

Dad patted me on the back as he walked to the car. All I could think of was that my fish had a tremendous will to live. When I thought of that, I found that I was kind of glad he got away. He deserved to live.

I pulled my straw hat over my eyes and, as I began to fall asleep, I remembered all the other fish out there. The next time I hooked a big one I was darn sure I’d get him.

(Editors’ Note: Before rerunning to school this September, Mike Douglas proved himself right. First came a “warm-up”—a fighting 73-pound tarpon landed in only 33 minutes. Two weeks later a 125-pound hammerheads hit his line with lightning unexpectedness: an hour later Mike had landed him. The monster jewfish? “Next year,” says Mike.)

Photos recently surfaced of the old pier on the beach of Patrick Air Force Base. These photos were likely taken in the 1960’s and early 1970’s before a hurricane took the pier down to ruins. Do you remember fishing this iconic pier? We’d love to hear about it. Please email webmaster@coastalanglermagazine.com for any stories or photos.