Over 40 years ago, in the early 70’s, the Bulldog BassMasters, a local club that I was a member of, fished a wide variety of lakes in northeast Ohio. One of them, Mosquito Reservoir was noted for its huge walleye population. To the locals, it was also known for being a highly productive largemouth bass haven.

In 1974, after a winter with record snowfall and heavy spring rains, water flooded many of the otherwise wooded shorelines of the sprawling 7,850 acre reservoir. As the water warmed and failed to recede, bass moved into these areas to spawn alongside the trees.

Our boats were much smaller back then, and not everyone had an electric motor, so it became very difficult to fish the standing timber. Anchoring up, many of us climbed out of our boats and waded the shallow water, working our way between the trees and dropping our baits near their base.

Bass were everywhere! Although we didn’t catch any huge fish, we caught plenty of numbers, and for most of us, we didn’t realize we were part of the new “flippin'” craze.

The history of flippin’ actually goes back another 20 years – back to California in 1956 when 19-year-old Dee Thomas, already an accomplished angler, witnessed some outstanding stringers of bass taken by two Clear Lake fishermen, O. C. McGee and Claude Davis, who had perfected a technique known as “tule dipping.”

Using 12’-14’ Calcutta bamboo rods, strung with 110-pound-test shock cord, and baited with a black striper jig with a double rubber skirt, the two fishermen could easily swing or flip the bait back into the tules and catch the many bass in these sheltered areas.

Dee Thomas was impressed but he didn’t like the bamboo rod and soon replaced it with a 12’ model fashioned out of a hollow measuring stick used by phone company employees. Instead of a reel, 110-pound test shock cord was threaded through the hollow, fiberglass rod and affixed to the butt. From the tip of the rod extended another 4 1⁄2’ to 5’ of cord with 2’ or 3’ of 30-pound monofilament tied to the black striper jig.

Eventually Dee replaced the measuring stick with a 16’ surf rod produced by Fenwick that he cut down to 12’. He considered this the “ultimate flippin stick”. Entering and winning a number of tournaments with his partner Frank Hauck, he was asked by Wayne Cummings of the old Western Bass circuit to put reels on their “dippin” rods. That was fine with Dee, and soon afterward, to his delight, he was able to peel line off his reel in order to make longer flips. Soon, the winning team of Thomas and Hauck, along-with their 12’ flippin’ sticks were becoming legendary. Other participants complained to Wayne Cummings that the 12’ rod provided an unfair advantage, so he again spoke to Dee about shortening the length of the rod.

Dee felt he could still control the bait and provide a strong hook-set with a 7 1⁄2’ rod. What many thought would be taking away his advantage soon proved to do just the opposite. 7 1⁄2’ worked perfectly.

Soon afterwards, Dee met Dave Myers who worked for Fenwick and over time, became a student of flipping. Eventually, as a result of their relationship, Fenwick became one of the first companies to actually manufacture a flippin’ stick. It was a 7 1⁄2’ collapsible rod.

Rod lockers in those days were much shorter, as were many of the boats themselves. In order to fit in the average rod locker, the 7 1⁄2’ rods had to be Dee Thomas built in a collapsible form to reduce its overall length to about 6’ in the locker. Moving east to fish some of B.A.S.S. events, the question of rod length once again surfaced and Ray Scott, along-with Harold Sharp, approved the 7 1⁄2’ length for their tournaments, and just to be on the safe side, allowed up to an 8’ length to be added to all future tournament rules.

Dee Thomas had a philosophy that involved three principles:

1. there are always some fish in shallow water;

2. a shallow fish is a biting fish;

3. the trick to getting them to bite is strictly presentation.

For Dee Thomas, the March 1975 Louisiana Invitational at Toledo Bend was an unmitigated disaster. Not only had he been intimidated by fishing against the much heralded superstars of bass fishing, but he did not fish even close to his abilities. For a western angler used to sparse cover, the abundance of standing timber at Toledo Bend only made his visual brand of fishing more difficult.

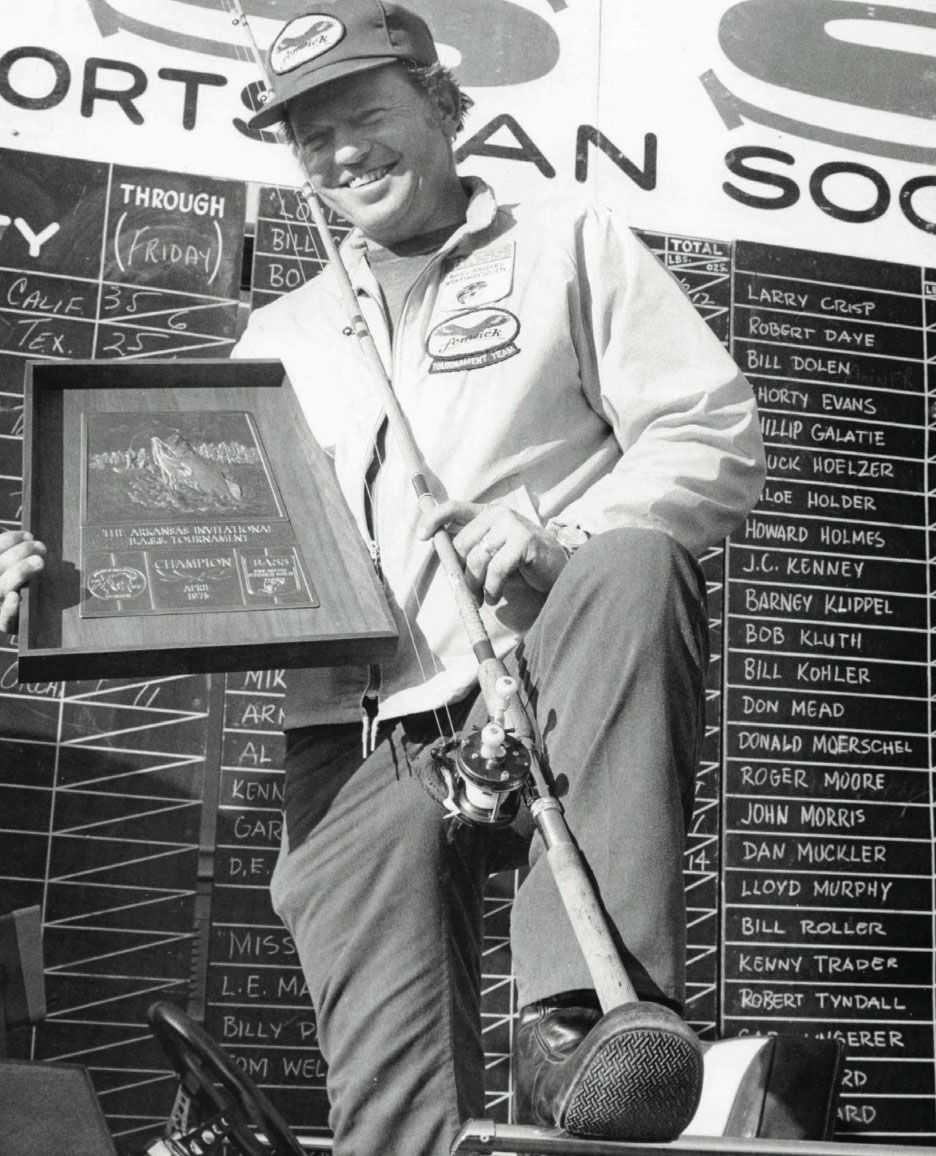

Convinced he could do better, he fished the next B.A.S.S. event on Bull Shoals. It proved to be an eye-opening experience for the rest of the bass fishing world. Faced with a tough bite, Thomas put on a masterful display of flipping’ domination.

Although his stunning victory could have set the stage for a B.A.S.S. career, he wasn’t interested. In his mind he had proved enough and felt perfectly content to compete on the western circuits. For the sake of flippin’ history, other personalities were ready, willing and eager to hit the road east.

The fascination with flippin’, and later the addition of pitchin’ took the fishing world by storm and today, over 40 years later, it continues to be one of the most important techniques used by fishermen the world over.

*Excerpts for this article were taken from the November 1995 November issue of BassMaster Magazine, written by Michael Jones.