Tom Champeau – Pisgah Chapter of Trout Unlimited

In late September 2024, Hurricane Helene damaged roads, trails, foot bridges, and historic buildings of the Cataloochee Valley in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP). The valley did not open to visitors until April 2025 and the valley road remains closed past the horse camp entrance as much of it was washed away leaving deep holes in many places. Rough Fork flows along this road and the damage will take a while to repair. Trails, the campground and most backcountry campsites reopened by summer, and Cove Creek Road that visitors take to enter the valley is in great shape.

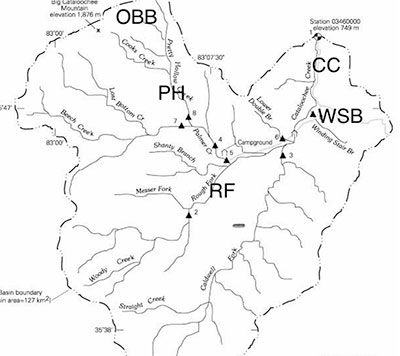

As part of a long-term monitoring project, GSMNP Fishery Program staff, seasonal interns that Trout Unlimited (TU) chapters in TN and NC help fund, and TU volunteers annually sample 43 sites across 24 streams in the park to evaluate trout populations and ecological health of aquatic communities. In July 2005, volunteers from the Pisgah and Land O’ Sky chapters helped sample streams within Cataloochee Valley (see map).

Streams were sampled using a standardized protocol to collect fish from a 100-m section blocked off by nets to contain all fish in the section. Depending on stream width, 1 – 3 backpack electrofishing devices that generate high voltage are used to apply electrical current into the water to temporarily stun fish allowing technicians to collect them with dip nets. Each section is sampled three times which provides an estimate of the total number of fish in the section. Scientists with the University of Tennessee assisted with sampling and collected salamanders that were also stunned during electrofishing.

Cataloochee Creek (CC), Winding Stair Branch (WSB), Rough Fork (RF), Pretty Hollow Creek (PH), and Onion Bed Branch (OBB).

Rough Fork (elevation–2,700 feet, just upstream of the Caldwell House), had a sympatric mix of rainbow, brown, and brook trout. Although high flows changed the stream bed considerably, trout abundance was similar to past years with good numbers of young-of-the-year (YOY). Pretty Hollow Creek (elevation–3,500 feet, 800 feet above Rough Fork) had a mix of rainbow and brook trout. High flows changed channel morphometry, but bank erosion, tree loss, and sedimentation were minimal. YOY brook trout were abundant. Onion Bed Branch (a tributary of Pretty Hollow Creek at 4,200 feet elevation) had a high abundance of brook trout. High elevation streams typically support only brook trout (allopatry). High flows caused minor changes in some stream habitat. Throughout the valley, the worst impacts occurring where the loss of riparian vegetation next to roads and trails resulted in high erosion of stream banks.

GSMNP Fishery Supervisor Matt Kulp said that many of the streams his crew sampled so far this summer reflect abundance similar to pre-Helene levels with good brook and brown trout reproduction during fall 2024 soon after Helene, and strong rainbow trout reproduction during spring 2025. He said larger trout were less abundant in some streams, perhaps a result from high flows. High numbers of YOY fish reflects the resilience of trout to high water conditions.

Cataloochee Creek (elevation–2,400 feet) was sampled by the USGS gaging station to measure the Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI), adding to a database that estimates long-term fish population trends, and enables comparisons between other streams in the park and across the Blue Ridge ecosystem. IBI is a numerical expression based on species composition, richness, and diversity, and the absence/presence of native and non-native species intolerant to various water quality parameters. Despite the presence of non-native trout, this section of the creek reflected excellent ecological health, and showed no impacts due to Helene.

Several streams in the valley have been restored to remove rainbow and brown trout followed by stocking Southern Appalachian Brook Trout. Streams selected for restoration have a waterfall, cascade, or historic mill dam sufficient to prevent migration of non-native trout from downstream, high-quality habitat, and acidity levels tolerable to brook trout. Winding Stair Branch (elevation–2,700 feet) was restored in 2001 and this summer, brook trout were collected to remove a small section of adipose fin for genetic analysis. Understanding which brook trout donor stocks resulted in successful re-introduction informs future restoration projects. Advanced genetic analysis may also allow scientists to understand which genetic attributes (alleles) provide sufficient fitness to increase genetic diversity, sustain effective population levels, and allow adaptation as the climate warms.

The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC) also conducted sampling last summer to evaluate the effects of Helene on wild trout populations across Western North Carolina. Jake Rash, Coldwater Research Coordinator with the NCWRC, reported that his team of fisheries biologists conducted 255 samples of over 130 streams and documented trout presence in most streams although abundance may have declined in some. Jake asked TU chapters to help educate the angling public to not attempt to improve trout populations by moving fish from stream to stream. This practice is more common than you might think, and could harm fish populations by transporting diseases, parasites, and aquatic invasive species. Illegal fish transfers may introduce rainbow and/or brown trout into allopatric brook trout waters, or waters slated for native brook trout restoration, which involves considerable planning and effort by NCWRC, their partners, and volunteers.

Jake also said that flood-related impacts to stream habitat may affect trout reproduction and survival to adulthood (recruitment). Impacts on streams and their habitats are varied across the mountains, so future fish sampling will be designed to evaluate the recovery of trout populations after Helene. Jake’s early assessment parallels what many guides are saying:

“The fish are there, maybe down in abundance in some streams, but don’t expect your favorite areas to fish the same as before Helene.”

This summer’s intensive river clean-up activities to remove debris, including downed trees, caused a great amount of concern among guides, riverkeepers, anglers, biologists, and other advocates for healthy rivers. The operation of heavy equipment along river bottoms and apparent disregard to protect stream bank habitat and pre-existing “legacy” woody habitat were reported in many rivers and streams that supported not only trout and other fish, but protected hellbenders and endangered mussel species. The long-term impacts of these debris removal operations have yet to be fully evaluated.