Edited By: Bob Halstead, Florida Atlantic University

What do tarpon and honest politicians have in common? They both start out small and most never make it to be big fish. Some would say that at least one of these is a mythical creature, or those chasing tarpon with a fly rod know better – they both are. Our last article (‘Tis the Season for Tarpon) discussed the inner workings of the tarpon spawn. Now we’ll get into the toughest stage of the tarpon life cycle – the larval period.

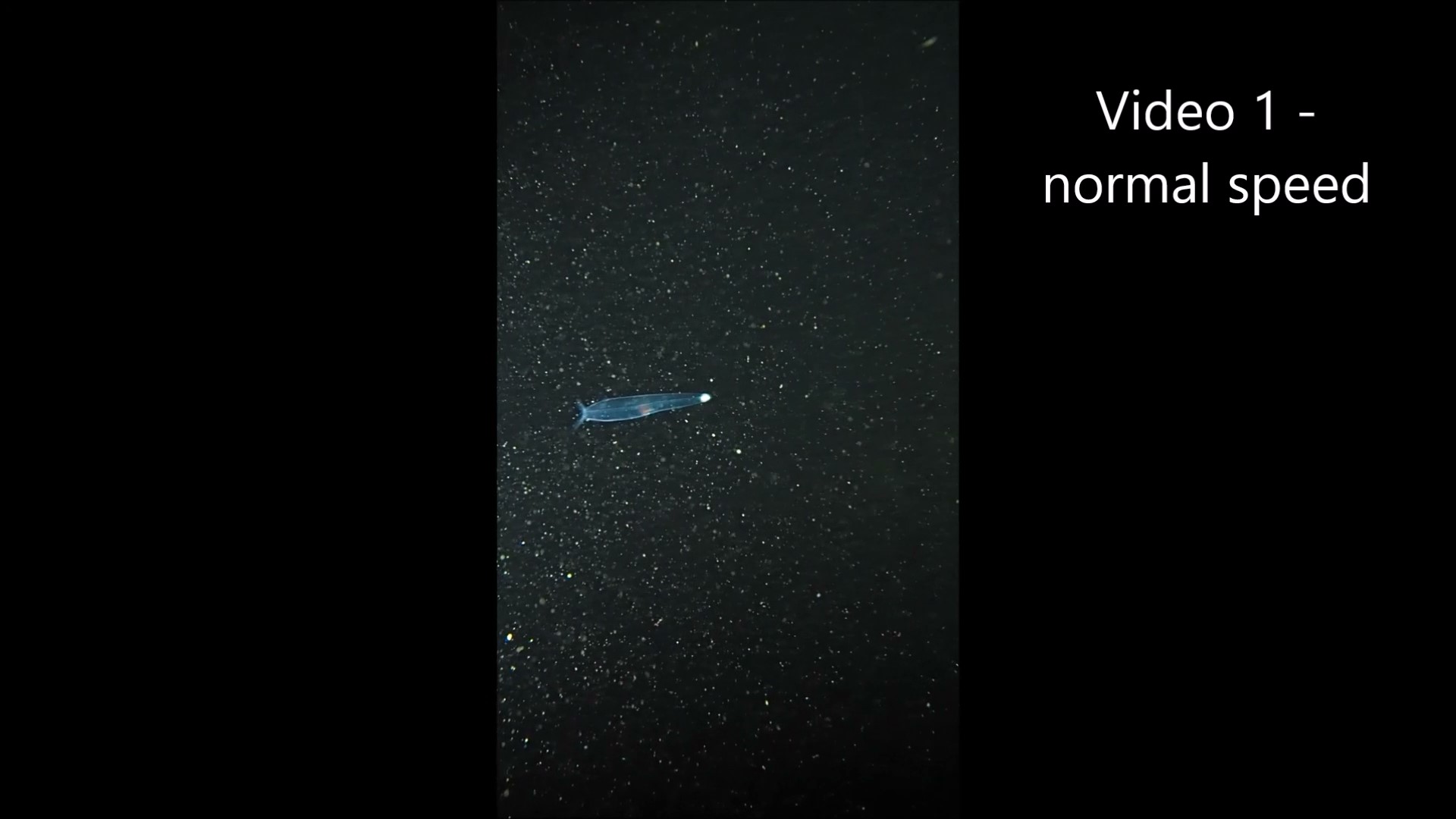

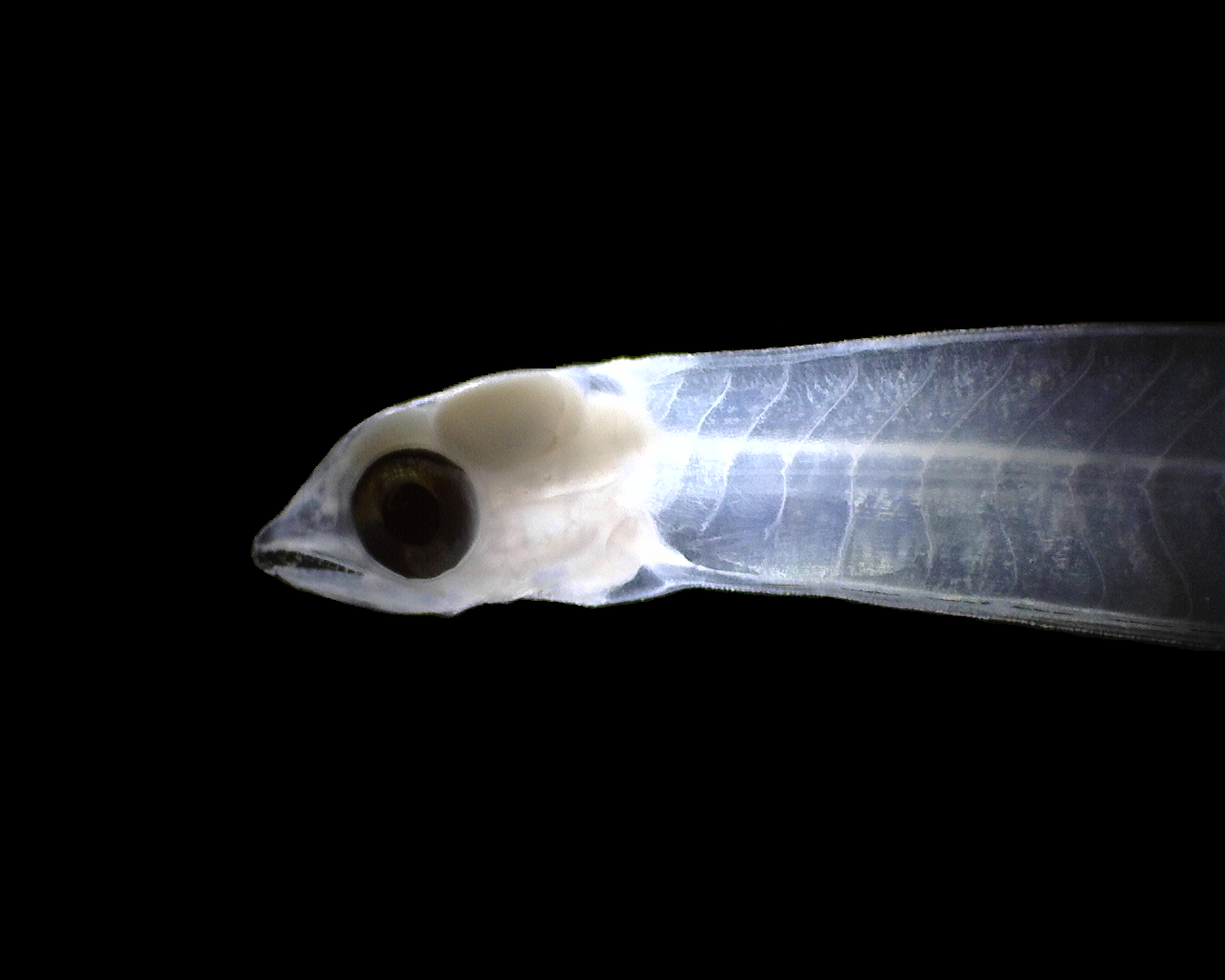

Adult tarpon spawn in the summer offshore by releasing their sperm and eggs into the open water – known as broadcast spawning. A small fraction of the eggs will be fertilized, eventually hatch and the larval stage begins and lasts about 30 days. A tarpon larva, known as a leptocephalus, is similar to the larva of eels, bonefish and ladyfish, but look more like a worm than a fish. Although they are large enough to be seen without a microscope, leptocephali are transparent, aside from a large eye and translucent muscle structure composed of myomeres. Leptocephali look extremely similar, but each species can be distinguished by counting the number of myomeres.

Early stage tarpon larvae give off quite the vampire vibe with their lack of body color, the development of long fangs, and their ability to see in the dark. The fangs may help with feeding; however, researchers still haven’t determined what exactly they eat. Some guesses include marine snow (the white specks made up of organic matter found drifting in the ocean), or rotifers, a nearly microscopic invertebrate. Another possible food source is the gelatinous “house” of tiny tunicates called appendicularians. These houses are used for filter feeding and are discarded when they clog up. Unlike most other fish larvae, leptocephali have rod-dominated eyes. This means they can see better in low light conditions. Eventually they will develop the ability to see color by developing more cone cells.

Since they are rather small, leptocephali are transported by currents – thank goodness since their parents left them offshore – but they do have some limited swimming ability. For the larvae that were lucky enough to survive in the open ocean, the currents deposit them inshore and close enough to an estuary to find refuge. One study in the Indian River Lagoon found that larval tarpon use their transparency and specialized eyes to their advantage by entering passes and traversing the estuary at night. This also coincides with summer high tides that carry the larvae deep into the backwaters of estuarine creeks and embayments. This ultimately becomes the nursery habitat where they will metamorphose into juveniles resembling the miniature version of their adult counterparts.

The further into the creeks the larvae are transported, the closer they are to human impacts, such as nutrient runoff, changes in waterflows or even total habitat loss due to coastal development. Because larval transport is relatively random, some tarpon can end up in natural creeks, while others find their way into marinas or golf course ponds where they are less likely to survive. Since tarpon mature much later than other species (~10 years), they depend on the survival of early life stages. By supporting fewer juveniles through to maturity, degraded nursery habitats can have devastating impacts on the tarpon fishery.