By Erika Zambello:

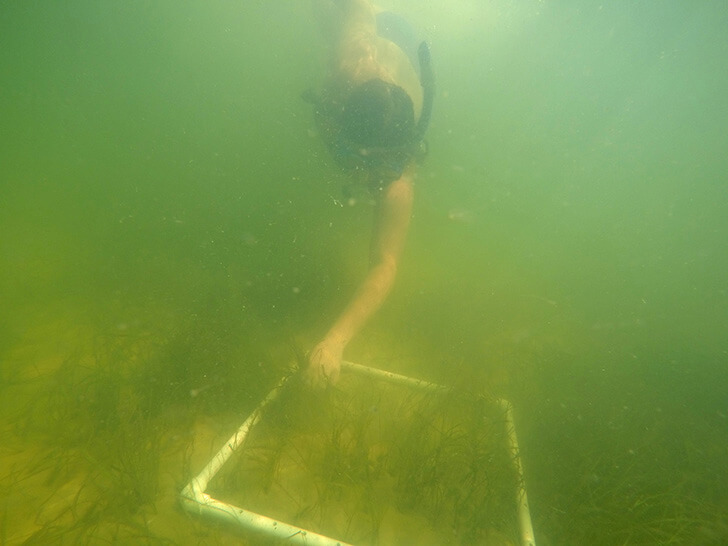

Monitoring Coordinator Brandy Foley stood at the Pilcher Park boat ramp, watching clouds gather over the Choctawhatchee Bay. She and other Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance (CBA) staff had just finished another day of measuring seagrass abundance and escaped the water just before a summer storm unleashed wind and rain across the horizon. Throughout the morning and into the afternoon, three of them hopped in and out of the boat at each study site, pulling on snorkels and masks to dive into shallow water and take stock of the bay’s seagrass. Throughout the year, the CBA team will complete close to 40 seagrass survey sites.

Seagrasses form a critical component of life in the Choctawhatchee Bay and throughout Florida. They are a direct food source for sea turtles and crabs, provide habitat and protection for juvenile sport fish species, like sheepshead and redfish, while increasing water clarity and dissolved oxygen content. seagrasses reduce shoreline erosion, current, and wave intensity. In fact, 70 percent of Florida fishery species spend at least part of their lives in the safety of seagrass beds.

“Not only are these seagrass beds important to the organisms that use it as a source of habitat,

Unfortunately, the bay has been losing seagrass since sporadic measurement began in the 1950s. Seagrass needs clear water to capture the sun’s energy for photosynthesis, and cloudy water due to sediment runoff or nutrient-caused algal blooms can kill them. Boats driving through seagrass beds can rip out the stems, creating long prop scars visible from the air. A report conducted between CBA and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute (FWRI), estimates that in 2007 seagrass in the Choctawhatchee Bay had decreased by 55 percent.

Foley and her team continue to monitor the trends, while her partners at CBA take aim at reducing pollution and sedimentation that threaten seagrasses. July found Restoration Coordinator Rachel Gwin hip-deep in Alaqua Bayou, building an oyster reef to reduce shoreline erosion. Near Destin, Education Coordinator Brittany Tate worked with a group of students from the Boys and Girls Clubs of the Emerald Coast. On hands and knees, the kids planted smooth cordgrass into burlap bags full of soil, future components of a living shoreline along Mattie Kelly Park. Once these salt marsh grasses take root, they will provide additional habitat while reducing pollution and sediment runoff.

Throughout the heat of the summer and into October, Foley and her team will continue their surveys. In an effort to update estimates in the Choctawhatchee Bay, CBA works closely with the FWRI to collect extensive data on seagrass, water quality, and sediment; part of a larger Florida Panhandle-wide estuary study. The more seagrass we as a community can help recover, the healthier our Choctawhatchee Bay will become!