Today’s North Atlantic swordfish stock is fully rebuilt and maintaining above-target population levels. But there’s work to be done to ensure management measures better support the fishing industry.

Swordfish. Credit: Shutterstock/Joe Flynn.

Today’s North Atlantic swordfish population is a great fishery rebuilding story.

Twenty years ago, this predatory fish was in trouble. Their population had dropped to 65 percent of the target level. This means there weren’t enough North Atlantic swordfish in the water to maintain their population in the face of fishing by the many countries who share the resource.

Fast forward to 2009 and the international commission that manages species like swordfishdeclared the Northern Atlantic stock fully rebuilt. That announcement came a year ahead of the 2010 target date set in the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna’s (ICCAT) 10-year rebuilding plan.

“If it’s U.S.-harvested swordfish, consumers can feel confident it’s a smart seafood choice,” said Rick Pearson, NOAA Fisheries fishery management specialist. “We should reward our sustainable stewardship practices at the seafood counter.”

Rebuilding an Important Population

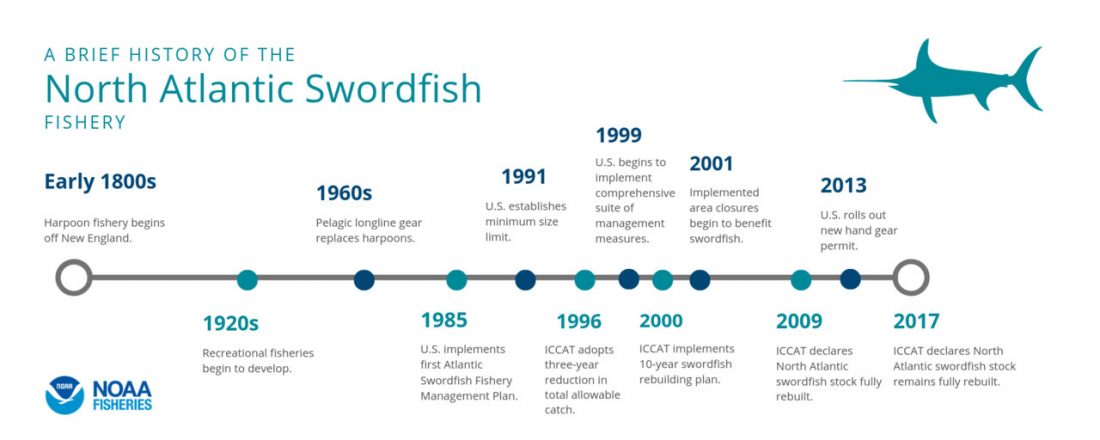

Efforts to restore a dwindling population of North Atlantic swordfish date back to 1985 when NOAA Fisheries implemented the first U.S. Atlantic Swordfish Fishery Management Plan. This plan reduced the harvest of small swordfish, set permitting and monitoring requirements, and launched scientific research on the swordfish stock. Minimum size limits and enforcement processes came shortly after when ICCAT issued its first recommendation on swordfish in 1990.

Despite these and other management strategies implemented over the next eight years, the stock continued to suffer. By the late 1990s, the average weight of swordfish caught in U.S. waters had fallen to 90 pounds, a drop from the 250-pound average fishermen enjoyed in the 1960s. This was in part because the population decline meant fishermen were catching younger fish.

What ultimately reversed their downward course was the broad suite of actions built up by the beginning of the 21st century.

“There is no one measure that could have brought this population back from the decline,” said Pearson. “Sustainable fishery management requires a comprehensive science-based approach that considers the biological needs of the fish population, the health of fisheries, the fishing industry, and coastal communities.”

In the United States today:

• A limited number of vessels can target swordfish commercially with longline gear.

• All fishermen must abide by minimum size limits, and many must also abide by retention limits.

• Closures prevent pelagic longline fishing in waters with historically high levels of bycatch species, including undersized swordfish.

• Satellite tracking systems are mandatory on some vessels that target swordfish.

• The use of circle hooks is required in commercial fisheries to increase the survival of sea turtles and other animals caught accidentally.

• Commercial fishermen must attend workshops where they learn to properly handle and releasebycatch, including undersized swordfish.

• Observer programs provide fishery scientists and managers with needed data.

Leading the International Community

Some of these measures can be traced back to the ICCAT rebuilding plan, but many are the result of U.S.-led efforts to protect swordfish, reduce bycatch of other species, and sustainably manage fisheries that interact with swordfish.

Pearson and others also point to the key role the U.S. commercial fishing industry played in helping to establish these domestic efforts and supporting greater international collaboration.

“The United States led the charge internationally to adopt measures to recover North Atlantic swordfish,” said Christopher Rogers, director of International Fisheries. “We pressed our international partners to adopt measures U.S. fishermen were already practicing, such as catch limits, minimum sizes, recording and reducing dead discards, and appropriate observer coverage. Strong U.S. leadership helped ensure the international community shared the burden for rebuilding this iconic species.”

Support for a Valuable U.S. Fishery

In the decade since ICCAT first declared that North Atlantic swordfish are not being overfished, the United States has seen a fall in its total annual catch. In 2017, U.S. fishermen caught just 14 percent of the total swordfish catch reported to ICCAT.

There are several reasons for this decline, says Pearson, including rising fuel prices, an aging commercial fleet, and competition from often lower-quality imported frozen products.

To help more U.S. fishermen take advantage of our national ICCAT-allotted quota, NOAA Fisheries has made several changes in the last decade to commercial and recreational restrictions, such as:

• Removing vessel size and horsepower restrictions on pelagic longline permits.

• Increasing retention limits on some permits.

• Launching a hand gear permit, allowing fishermen to participate in the fishery without spending more to buy a longline permit from another vessel.

• Making it easier for fishermen to get and renew permits.

But there is more work to be done to ensure our regulatory program is effective in both maintaining swordfish populations and supporting the fishing industry. We are currently examining whether some area-based and gear management measures that affect swordfish fisheries could be modified in light of the success of a program that has reduced bluefin tuna bycatch.

“The U.S. fishery management process is a dynamic process,” said Pearson. “Protecting the North Atlantic swordfish population from overfishing while ensuring fishing opportunities for our recreational and commercial fishermen requires the best available science and responsive management.”