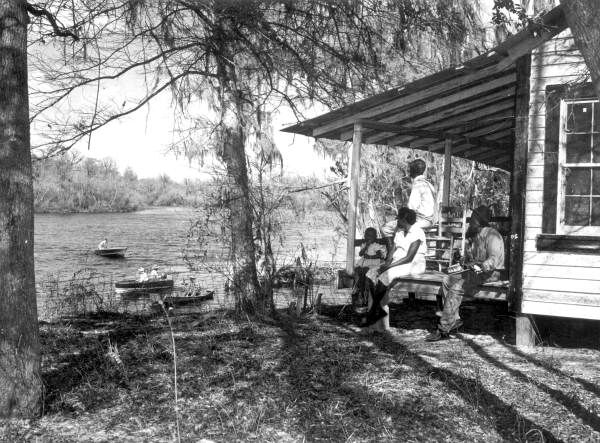

Florida Waterways

“The Mouth of the Suwannee River”

By Kevin McCarthy

After the magnificent Suwannee River has meandered some 265 miles from Georgia in ever-increasing speed, it empties into the Gulf of Mexico, pouring billions of gallons of fresh water into the salty Gulf. It has been doing this for hundreds, maybe thousands of years.

Advocates for drier sections of the state further south have enviously eyed all that fresh water pouring into the Gulf and have suggested that much of it be diverted to quench the thirst of those living in South Florida, and even to irrigate the fields there. Those same advocates, have argued for a similar pumping of fresh water south from the Ocklawaha, the Withlacoochee, even the St. Johns, but so far defenders of our rivers have prevailed. The problem is that the growth in South and Central Florida sites is projected to outpace available ground-water in the relatively near future and their legislators will again press for a diversion of our rich waters to the south.

This last part of the Suwannee is part of the Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge (LSNWR), established in 1979, and consisting of 53,000 acres in one of the largest undeveloped river-delta estuarine systems in the United States. It includes twenty miles of the Suwannee River estuary, and twenty miles of coastline. The refuge is open all year round for wildlife observance, hiking, and photography. The fishing, hiking, and birdwatching in the area are very, very good.

Islands near the mouth of the river have a fascinating history. Hog Island, for example, is a federally protected property and wildlife sanctuary. Probably named for the wild hogs that used to live on the island, an early Spanish mission to the Native Americans used to be there. Called Cofa in the early 1600s by the Spanish, the site would have been strategic for resupplying soldiers and missionaries, as well as convenient for off-loading ships in the Gulf.

Cat Island in the estuary, has been the site of experiments by school children from Dixie County, who grow shellfish like cherrystone clams. The students pull in the mesh bags from the water, wash the bags thoroughly with fresh water, clean the growing clams, put them into larger bags, and return them to the water. The students monitor the salinity of the water, its temperature, and its purity. They will eventually harvest the clams, sell them to restaurants, and keep eighty percent of the money – with the other twenty percent going to the county for such programs. Not only do the students earn some money, but – more importantly – they learn the value of the estuary and the importance to keep it pure.

Big Belcher Island, later called Odlund’s Island, was the home of one of the legendary personages on the river: Eric Odlund, the so-called “King of the Suwannee.” Before he died in 1941, he and his wife, Luella, raised many children, some of whom returned from living on the mainland, to eke out a living on the island.

If you fish or boat near the mouth of our great river, you will see unspoiled nature around a rich estuary, which has been home to millions of sea creatures, including many species of fish, for thousands of years.

Kevin McCarthy, the author of Suwannee River Guidebook 2009 – (available at amazon.com), can be reached at ceyhankevin@gmail.com.