By Kelsey Woody

The Appalachian Mountains formed before eyes existed to see them. They towered high as the Himalayas long before there were legs to hike their peaks or trees to define their hazy, blue silhouette. For most of their lifetime, the Appalachians simply existed—unseen and indifferent, but by no means stagnant. Over the course of one billion years, the Appalachians were built in dynamic bursts as shifting continents repeatedly collided and broke apart, crumpling rock layers into tangled masses and lofting them high above the surrounding landscape. Young mountains were sanded and shaped by water and wind, but there were no root systems to crumble their layers into soil for the first half of their yawning lifetime. The Blue Ridge Mountains are one of few surviving ranges from the very first Appalachian mountain-building event, making them true elders even among their mountain peers. Even with time-smoothed edges, compacted by stories and myths, the Blue Ridge Mountains defy comprehension. They were here when we appeared, and they will persist long after we are gone.

to the bumps on the snout of a hornyhead.

When mountains rise, the life inhabiting them is forced to rise too, often isolating species or forcing them to coexist. The divergence or combination of streams can do something similar, occasionally kicking off entirely new evolutionary paths. Consequently, the uplifted, river-sculpted Appalachians may have been a crucible for diversification of freshwater species over Earth history. Unfortunately, the study of extinct mountain fish species poses an acute scientific challenge. Lakes, with their calm waters and rapid sedimentation rates, are much better environments for fossil preservation than babbling brooks. As a result, the search for intact specimens from ancient mountain habitats takes no shortage of patience and a whole lot of luck.

Despite the spotty recollection of rocks, we still know quite a bit about ancient Appalachian ecosystems, including some of the earlier fish to call these mountains a home. Freshwater fish first pop up in the fossil record around 420 million years ago, during a chunk of Earth history in which fish are so common and varied that Earth historians literally refer to it as “The Age of Fishes”. However, to find the oldest preserved freshwater fish in the Southern Appalachians, we must travel forward in time a whopping 200 million years—to the age of the dinosaurs.

By this time, restless tectonic plates have slammed all of Earth’s landmasses together into one giant continent, then have promptly begun to rip them apart all over again. That stretching and tearing generated a smattering of lakes across North Carolina and Virginia that began busily depositing mucky sediments jam-packed with freshwater fossils. In the oldest of these bygone habitats, a little freshwater fish named Dictyopyge macrurus (or D. macrurus, for those of us without a national spelling bee title) thrived.

To meet D. macrurus, let’s set out together to a lake in modern-day Virginia on a hot, humid day approximately 230 million years ago. Ferns brush against your face as you bushwhack through brush, avoiding the pointy spindles of conifers as you make your way to the shaded water’s edge. You lean against the squat, woody trunk of an odd, short plant topped with palm-like fronds, positioning yourself slightly back from the lake to avoid casting a shadow as you scan the placid surface. You watch patiently until you catch the nearly imperceptible flick of a fin that gives away the fusiform shape of a small fish, holding impossibly still despite the gentle motion of the water. Now, with your eyes tuned, you pick out a second fish, then a third, camouflaged in the murky depths. Insects fill the air with a low drone, and a tiny fly ricochets across the serene surface, leaving no ripple in its wake. You’ve paid careful attention to the bulky midsections, long abdomens, and intricate, translucent wings of this bug, and quietly remove a Parachute Adams from your gear, attaching it to your line. You cast, flicking the line out, back, out again. Eventually, you coax a curious fish—no more than five inches across—to nibble your line and quickly yank back, locking it onto your hook. As you reel your first catch in, you sigh. Another D. macrurus. Too small to make a good meal, but they sure are fascinating to look at. Holding it firm in your hands, you take in its sleek, elongate body, covered in striking diagonal rows of hard, gleaming scales. As it opens and closes its mouth, you catch glimpses of tiny, uniform teeth. But the truly unique feature of D. macrurus is its bizarre skull. A series of flat ridges and bumps weave together and split apart in unpredictable patterns, creating a strange zebra effect across its skull, culminating in a snout ornamented with a chaotic mosaic of tiny nodules. You scratch your head, wondering what on Earth those could be useful for as you lower it gently back into the water. As you begin to stand, you catch a slithering motion in your periphery and drop low as a behemoth reptile swims lazily into view—its narrow, crocodile-like snout parting the water in advance of its twenty-six foot long, armored body. A fiercer predator has claimed this lake—it’s time to head home.

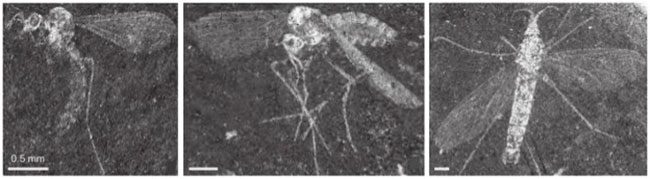

*The name of this article (“Time Flies”) is inspired by a scientific publication on Triassic insects (Blagoderov et al., 2007) from which the fossil insect images in this article were selected.

Kelsey Woody is a geologist from Asheville, NC, currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Earth Science in St. Louis, MO. Though her graduate work focuses on understanding the origin of volcanic rocks from the Eastern Pacific, she grew up fishing in the Smokies and was delighted by an opportunity to write about the fascinating geologic history of the Blue Ridge. To reach her with questions about ancient fish (or the Eastern Pacific), email kelsey.woody22@gmail.com.