By: Eric Schneider, Zach Zuckerman, and Aaron Shultz with the Flats Ecology and Conservation Program, Cape Eleuthera Institute and Karen Murchie, with the College of The Bahamas

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]onefish are a popular sport fish in The Bahamas, attracting anglers from around the world. The catch-and-release bonefishing industry generates over $140 million annually for the archipelago. Other activities that attract people to The Bahamas, however, may pose a threat to the fragile near-shore habitat that is crucial for bonefish survival. Development of resorts, marinas, shipping channels and the removal of mangroves contributes to the degradation of shallow-water ecosystems across The Bahamas and a loss in bonefishing habitat.

Bonefish mainly inhabit shallow coastlines and depend on mangroves and healthy seagrass habitats for foraging for food, protection from predators and daily movements and migrations, but then migrate to deeper water to reproduce. A few days around the full or new moon, hundreds to thousands of bonefish may gather in choice near-shore locations and form a circular school known as a pre-spawning aggregation. When night falls, the school will move into deeper water (typically at the edge of the ‘wall’ or continental shelf) and begin to spawn. If successful, the eggs and then larvae circulate in oceanic gyres until they are large enough to swim towards shore and recruit to a suitable habitat. If their foraging and spawning habitat is jeopardized, so too could be the fishery.

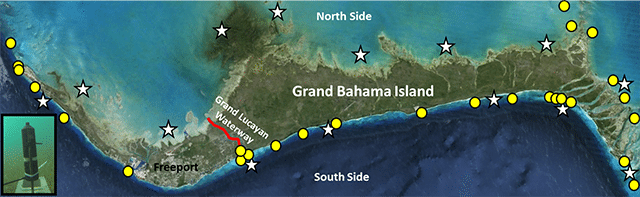

Grand Bahama Island is an example of the habitat mosaic that is now common across The Bahamas- prime bonefish habitat fragmented by human development. The construction of the Grand Lucayan Waterway bisected the island, connecting shallow bonefish flats on the north side to deeper spawning habitat on the south side, yet it was unclear whether bonefish utilize this corridor for spawning migrations. Identifying not only where bonefish aggregate to spawn, but also key migration routes, is critical to timely protection of these habitats to secure the recreational fishery.

To identify bonefish movements through the canal, the Cape Eleuthera Institute, the College of The Bahamas, the Fisheries Conservation Foundation, the University of Illinois, the Bonefish and Tarpon Trust and the Bahamas National Trust have teamed up with guides from H2O Bonefishing and North Riding Point Club, completing a diverse team of researchers, stakeholders and anglers. The team employed acoustic telemetry, a process that involves surgically implanting bonefish with a small transmitter that emits a unique signal that can be detected by a receiver when the fish swims nearby. The receivers are strategically placed around the island in shallow areas through which bonefish are thought to move, including the Grand Lucayan Waterway. As the fish move throughout the array of receivers, a virtual ‘map’ can be formed showing the exact movement patterns of each tagged fish around Grand Bahama Island.

To date, 30 bonefish have been implanted with acoustic tags, and over 26,000 individual detections have been recorded by receivers. Bonefish have been tracked through the canal, but have also moved east and west along the north side of the island, travelling more than 50 miles to reach spawning aggregations in deeper waters on the south side of Grand Bahama Island. This year, the project has expanded with the aim to locate spawning aggregations around the island.

There is significant coastal development planned for the future in Grand Bahama, some of which is in close proximity to potential spawning areas. Large-scale development could be extremely detrimental to bonefish survival and reproductive success due to factors such as mangrove loss, increased sedimentation leading to poor water quality, and boat traffic. However, there has been some recent interest in establishing a national park and marine protected area. Ultimately, this acoustic study will provide necessary information to direct such conservation efforts towards protecting these spawning sites and the corridors fish use to reach them.

The Cape Eleuthera Institute is a non-profit organization whose mission is to utilize meaningful research as a tool for outreach and education. For more information on bonefish research in The Bahamas, visit www.ceibahamas.org and www.blog.ceibahamas.org. For more information on sponsoring a Grand Bahama bonefish and your chance to win a 5 night/4 day bonefishing trip for two, visit www.fishconserve.org/bonefishcontest/.