Florida Waterways – “Fishing in the Bay of Fundy”

CAPTIONS:

The Cape D’Or Lighthouse compound

Cliffs at Bay of Fundy

Map of Bay of Fundy

A Mi’kmaq making a canoe

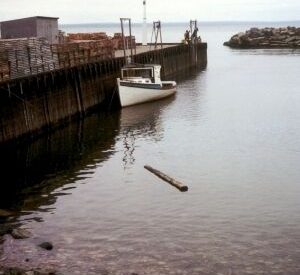

Bay of Fundy at high tide

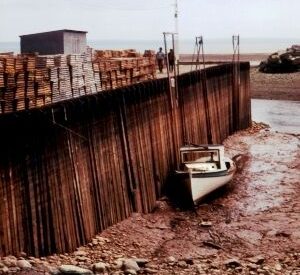

Bay of Fundy at low tide

Having recently spent part of a week living at a lighthouse along Canada’s Bay of Fundy, my wife and I marveled at the huge flux in tides, visited a 300-million-year-old fossil site at the Joggins Cliffs along the Bay, and learned about fishing in the waters there. After flying to Halifax in Canada’s maritime province of Nova Scotia, and driving around the Bay for about three hours, we arrived at Cape D’Or Lighthouse, for an unusual experience far away from the heat of Florida in the summer.

We spent three nights at the lighthouse, knowing that the Bay has very thick fog from time to time. And, in fact we experienced such a fog one day, when we could not see the Bay at all. A foghorn at the site could warn ships in the Bay of the huge rocks along the shore, but we learned that officials were going to dismantle the foghorn and take it away, perhaps reasoning that mariners no longer needed such an “old-fashioned” aid to navigation.

Twice a day, the tides in the Bay can reach over fifty feet, or as tall as a five-story building. The estimated 175 billion tons of seawater that rushes in and out, are more than the flow of all the world’s freshwater rivers combined. Boaters and fishermen have to be very careful with the force of that water rushing in twice a day, but persistent fishermen can catch cod, flounder, haddock, halibut, and even an occasional shark, especially those species that like cold water. And lobster-catching is one of the major income generators for resourceful fishermen. The tides there are the highest on Earth, especially during the fall harvest moon and around the autumnal equinox.

We learned that the Bay’s tides are so huge, because of the conical shape of the waterway, and the way that the tidal bores move in sync with ocean tides. Some places in the area can be very good vantage points for seeing the water rush in and out, but you have to time it just right, paying attention to the time of year, and daily tide schedule.

We learned from the maritime museum in Halifax how the Miꞌkmaq indigenous First Nations people have fished in the Bay for several thousand years, and how they have adapted their boats with new technology. We learned in the Age of Sail Heritage Centre/Museum in Port Greville, Nova Scotia, how boat-builders built hundreds of large fishing boats along the nearby rivers that flow into the Bay.

Today in the waters there, one might see porpoises, seals, and whales, and many kinds of seabirds. All in all, the trip was very instructive and unusual, especially in the heat of the summer. Plus, if you have the time, a trip to Prince Edward Island over Confederation Bridge, the world’s longest bridge over ice-covered water, you can tell much about the Acadian People, descendants of French colonists who settled there in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Kevin McCarthy, the author of The Black WACs of World War II (2019 – (available at amazon.com), can be reached at ceyhankevin@gmail.com.