[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ne of the most beautiful fish in our waters is also one of the most feared. Lionfish, highly prized as an aquarium fish for its billowing fins and tiger-like stripes, were once imported from far-away Pacific Islands. Like many other imported species, such as pythons and iguanas, some of these fish found their way into the wild where they are now competing with native species.

Lionfish were first discovered off the Atlantic coast of Florida in 1985. After doing numerous DNA studies, scientists believe the lionfish came from aquarium releases. Lionfish owners probably freed their exotic pets when they grew and started eating other fish in the tank. DNA sampling indicates the invasion comes from only 8 to 12 lionfish that survived release into the Atlantic Ocean. As research divers for the Mexico Beach Artificial Reef Association (MBARA), Carol and Bob Cox watched the lionfish invasion growing closer to the Forgotten Coast. Everyone hoped the winter waters would be too cold for lionfish survival this far north.

However, in September 2010, a lionfish was collected off the coast of Pensacola. In July of 2011, Bob and Carol Cox were diving the Empire Mica with friends when Bob spied a lionfish. The very next day, Carol saw one on the Red Sea Tug, a popular Panama City dive site. A few days later, while doing a survey for MBARA, Bob found a lone, small lionfish on the Progress Energy Reef, a shrimp boat intentionally sunk as a reef by MBARA.

They went back a few days later to photograph and collect the lionfish. The 5-inch fish was the only lionfish found on MBARA reefs in 2011 and didn’t look very threatening, but it was an ominous sign. In 2012, divers recorded 13 lionfish on the artificial reefs. By July of 2013, only halfway into the dive season, they have sighted 34 lionfish on the artificial reefs off Mexico Beach. Most of the lionfish are in water that is 90-feet deep or deeper, but they are appearing in shallower depths. They have been found by MBARA divers in the Car Bodies site that averages 60-feet deep, and in Bell Shoals at 24-feet deep.In addition, lionfish have been reported in Saint Joseph Bay, the mouth of the Mexico Beach Canal, and in a clump of seaweed near the beach at Cape San Blas.

Why are lionfish so successful? When the water is warm, they can breed every 4 days and their egg sacs are protected by a casing that is distasteful to marine life. With their exotic appearance, they do not resemble anything recognized by native fish as food; additionally they come armed with venomous spines that can cause pain to any attacker, including divers. Also, the lionfish that survived capture in the Pacific, a long journey to an American pet store, transfer to a private aquarium, and then dumping in an alien ocean, had to be some hardy stock.

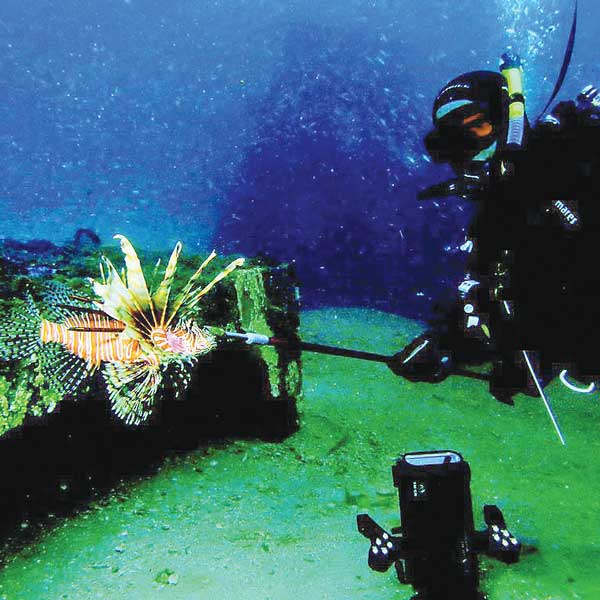

Lionfish are not aggressive; the spines are just for defense. When approached, they stand their ground, and if harassed, they either retreat or face the aggressor in a head-down position. This position directs the largest venomous spines at their assailant. Carol doesn’t advise trying this, but she admitted to using her camera to harass a lionfish to gauge its reaction. The lionfish didn’t attack, but instead assumed the head-down position, putting the long dorsal spines between the camera and itself. In other words, lionfish don’t chase swimmers in an effort to sting them. Most stings happen when a lionfish is defending itself from a diver spearfishing, or accidental contact, like when a diver reaches into a crevice for a lobster.

Besides the venomous spines, another large problem with lionfish is their voracious appetite. Lionfish are eating many native species, and may be competing for food with our local fishes. As part of MBARA’s research efforts, divers are collecting lionfish and analyzing their stomach content. They want to determine what lionfish eat in our local waters. So far, the largest part of their diet is blennies. Blennies are an easy target since they stay close to the reef and have small territories. Also found in the stomach of lionfish, were some small wrasses, an adult purple reeffish, and a juvenile barracuda. Juvenile snappers and groupers are just beginning to settle on our reefs, so the MBARA divers will watch to see if lionfish eat these important sport fishes.

Scientists have not figured out what controls lionfish populations in their native habitat. They are not found in great numbers in their native Indo-Pacific. Divers are currently the best way to control lionfish, but there are signs lionfish are thriving in depths beyond recreational diving limits. Sometimes lionfish are caught by fishermen, but this is the exception. Scientists are trying to find ways to trap or control lionfish without putting other species at risk.

Divers who want to help eradicate lionfish don’t need a Florida fishing license. The requirement has been waived by the Florida FWC. Divers must use equipment designed for lionfish removal, such as a handheld net, Hawaiian sling or pole spear. When using a spear, they must avoid areas where spearing is not allowed. (For more information, visit www.myfwc.com .) The best device MBARA divers have found to kill lionfish is a pole spear with a triple-prong. It is easier to remove a lionfish from a triple-prong than a barb head made to hold a fish on. Once killed, the lionfish can be left on the bottom or collected for consumption or research.

In some countries, divers are trying to teach native fish to eat lionfish by offering speared lionfish to larger predators. However, in Florida you are not allowed to feed marine life. This activity encourages sharks and large groupers to seek out divers as a potential food source, creating a dangerous situation. Bob and Carol saw this first-hand in the Bahamas when a gray reef shark stole a stringer of lionfish from a diver. The diver wanted to keep the lionfish for himself, but the shark easily won that battle.

And speaking of eating lionfish, you won’t believe how good this fish is until you try it. Many divers and fishermen forego this pleasure because of the venomous spines, but it just takes a few precautions to avoid them. Divers can purchase lionfish container systems online, or build their own. One inexpensive method is to use a plastic bucket with holes in the bottom, an X carved in the top, and a weight to keep it from floating. Lionfish can be speared, shoved into the bucket through the X, and the spear removed.

Once on the boat, put the lionfish in a cooler where they will be safely away from hands. When on shore and the lionfish are no longer flopping, scissors or poultry shears can be used to cut off the fins where the venomous spines are located. Then the lionfish can be prepared as you would any other fish. You can find numerous videos online that show you how to clean lionfish. Lionfish flesh is a delicate white meat with no fishy flavor. It can be cooked the same way you would cook any other delicate fish, such as flounder. It can also be eaten raw. The texture is perfect for sashimior sushi and has a mild, shrimplike flavor.

No article on lionfish would be complete without instructions on first-aid in case you do have an encounter. Most divers have learned what to do if they get stung by a lionfish. However, as lionfish invade our shallow waters, chances increase for encounters by snorkelers and waders. A lionfish sting is extremely painful and in rare cases can cause an allergic reaction with breathing difficulties. Heat breaks down the venom, so the affected area should be soaked in hot, not scalding, water for 20 to 30 minutes. If hot water is not available, consider carrying heat packs in your first aid kit.

On a boat, you may be able to get hot water from the cooling system of the engine. After soaking the injury, seek medical attention to prevent infection and monitor for serious adverse reactions. The public is asked to report their observation of lionfish. Data is collected by the United States Geological Survey as part of their Non-indigenous Aquatic Species program. By reporting your sightings, you can help raise awareness of how serious the invasion is. Lionfish can be reported online at http://nas.er.usgs.gov/sightingreport.aspx. The site asks for the location and date of the sighting and lets you give other details, like whether the fish was collected. You can also post photos of the lionfish. The database is also a great place to find out where lionfish have been reported and to see maps showing how fast they are spreading. (Carol Cox is retired from the Air Force and spends much of her time volunteering for the Mexico Beach Artificial Reef Association. Carol has been certified as a fish identification expert in the Tropical Western Atlantic by the Reef Environmental Educational Foundation.

For more information on MBARA, go to www.MBARA.org.

Carol Cox

850-899-1728

ccox@mchsi.com