I have never been so afraid that I know what’s happening and wanted so desperately to be proven wrong. What my big-picture understanding of fisheries management and the sum of fishing effort tells me is that this season we’re living out a terrifying end-game of many years’ profoundly flawed regulatory thinking.

Of course, my inner fisherman tells me I ought to take all of this in stride—that much of what I think I know is pure crapola, that fish are just running late or that we fishermen have a tendency, in recalling previous seasons, to shift the actual timeline on which things developed back against the calendar. The fish—striped bass and fluke, tuna and sharks—will come the way they do every season, maybe a bit behind an average year’s schedule.

Water has been cold, ponderously slow in warming up. When I talk to other fishermen about water temp, hear that a few guys have observed temps flirting, for short periods, with the 60-degree mark, I remind myself that surface temp is the unit of measurement among fishermen—and that it’s down-temp (a reading 20 or 60 feet below) that sways fish. In my more optimistic moments, I must admit that if I were running on instinct and not calendar time, I’d probably swear up and down we were all fishing in the time-span formerly known as the third week of May.

What upsets that calmer, more measured applecart is the fact that, closing in on 20 years of fishing mindfully, I can’t remember another season that unfolded in the spastic, three-steps-forward-four-steps-back way this one has. Mother Nature changes perpetually, I remind myself. Then I consider that the science everywhere in the news is only working on, in its most credible hour, a 100-year data set: Only a complete buffoon of a scientist thinks that his 100 years out of 100,000 years represents the absolute, all-time, cycles-be-damned baseline for planet Earth. I am not, I realize, qualified to speak in absolutes: The fact that I have not fished a season that began thus does not mean it never happened. And lately, deciding that I’m a moron is how I do fisheries optimism.

Here’s one problem. I know we’ve pounded the living snot out of our striped bass resource—apparently to the extent that 90-percent of the bass folks I know are catching fall somewhere between 28 and 32 inches. I’ve spent two years beating that notion into the ground head-first. I know that some percentage of stripermen will dismiss me as an alarmist or a complete ass-clown when some quantity of big bass appears, seemingly overnight, out of thin air at Block Island or Montauk the first week of July like they have to various extents, since populations rebounded. This year, there will be as many less fish as we exterminated last season on those grounds—unless we end up with more bass that might, in previous years, have wound up somewhere else along the striper coast.

Another problem: Under the current fisheries management approach, regulators by statutory necessity deal with each species in an ecological void, with no mechanisms (scientific or otherwise) to account for the interplay between various managed species, the total available food supply, or—most importantly—for the fluid nature of fishing capacity and fishing effort. Here in 2015, a year of career-worst fluke fishing for even some of the the region’s foremost rod-and-reel slabmen, one of two things is going on: Maybe fish are either painfully late in arriving and unusually concentrated in geographic distribution (in other words few and far between) thanks, no doubt, to sluggish water temperatures and the conspicuous lack of anything worthy of the title “squid run” this spring.

Or, we are now feeling the longer-range impacts of the sheer number of draggers, NC, VA, MD, NJ, CT, RI, and MA, spending their entire winters towing between 40 and 50 fathoms more or less due south of us, dump-trucking trips of 10,000 pounds or 12,000 pounds to NC or VA (whether the vessels possess permits for those states, or simply lease quota from vessels in those states), or dumping somewhat smaller weekly aggregate limits in NJ, then CT, then RI, then MA, and starting over again, west to east, the following week. Maybe all the effort consolidated on the winter spawning grounds to our immediate south’ard—all the meat being extracted—is taking a serious @#$% toll on the bodies of summer flounder that might otherwise have moved inshore and populated our summer grounds.

Viewed a different way, in the new (last five years, give or take) squidless winter pattern, in the post-groundfish era, for those who don’t have a market, the capacity, or permits for winter sea herring, fluke are the one stock vessels from NC to MA are allowed to work on. The state-by-state view of fluke management/allocation is a bit misleading in that during the winter quota period (with the year’s largest trip limits and aggregate landings programs, the latter meaning vessels can land the entire week’s limit in one trip—ostensibly to avoid dead discards) precisely none of the fluke landed are state-waters fish; they’re federal-waters fluke, and overwhelmingly, with the climate-change data suggesting the summer flounder biomass is trending north and east, the vast majority of fluke harvested are dragged up between Hudson Canyon and Atlantis, between 30 and 50 fathoms. Essentially, 10,000-pound Carolina limits are harvested off RI and NY—as are most if not all the other limits feeding the dump-truck fisheries in each fluke state.

Sea bass? At last count, the ocean’s turning rotten with ‘em, and no one can keep squat, thanks to the massive statistical uncertainty about the quality of the sea bass data (of which there’s precious little)—the sum of which (uncertainty) is subtracted from the target quota. From there—down 30 or 40 percent from the original TAC—states must subtract their own inevitable quota overages, the product of ever- shrinking limits and seemingly boundless abundance, and voila: A regulatory death spiral…

Cod? Turn on 10 minutes of NPR and hide all the sharp objects in your house: That stock, thanks to the New England Council’s stillborn brainchild, the sector allocation scheme, which underwrote the wholesale slaughter of the last discreet breeding population of codfish in our part of the Atlantic, teeters on the brink of biological oblivion.

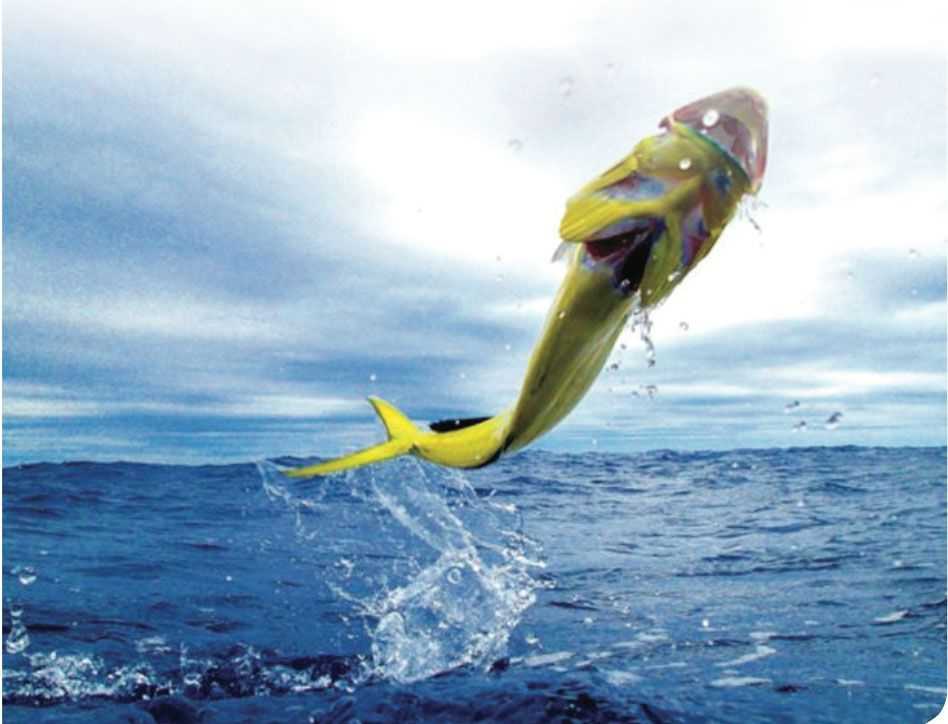

Here’s hoping for one rockin’ good tuna season in the canyons. Better yet, here’s hoping Mother Nature does what she does so flawlessly: Pours on a bumper crop of fish—more and bigger fluke and more huge stripers than anyone has ever seen, plus 4-pound scup, some codfish, blues, bonito, and a surprise late-arriving run of squid thick enough to subdivide and build houses on. All that on July 1, the date this poor doomed op-ed lands in your hands: Another fish-pencil waxes moronic with a whole host of paranoid drivel about how the fishing sky is falling. Mother Nature Serves Crow to Fish Editor Harvey. It wouldn’t be the first time, and God willing, won’t be the last, either.