Paul MacInnis

Brevard County residents spoke loud and clear on November 8, 2016 when 62% of the voters approved the Save Our Indian River Lagoon ½ cent sales tax referendum. The tax is expected to raise $300 million over the next ten years for lagoon restoration. Collection of those taxes began in January. Now, a year after approval of the referendum, let’s look at what will be done to help our lagoon.

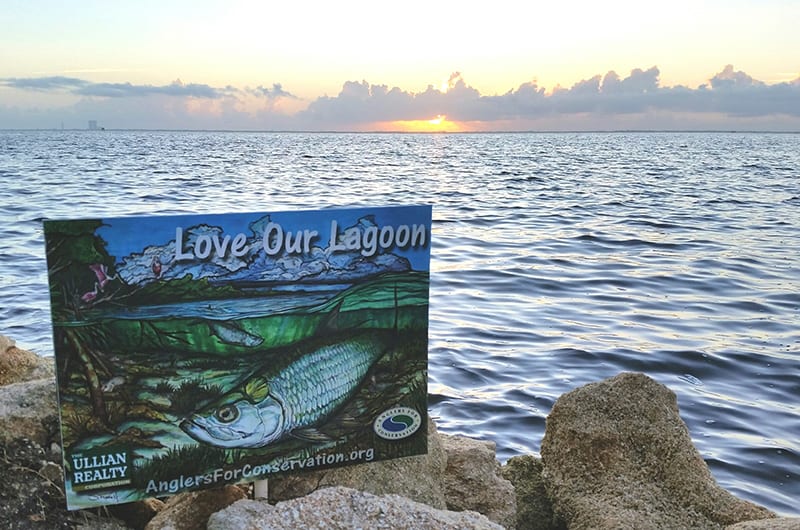

The Indian River Lagoon (IRL) is one of the most biologically diverse estuaries in America, but she is sick and needs our help. For decades nutrient pollution has leached into the lagoon through excessive fertilizer use, storm water runoff, septic system seepage and waste water treatment discharges. Years of nutrient accumulation led to an intense algal bloom in 2011 called the “superbloom’, and subsequent years saw recurring brown tides that clouded up the water, choked out seagrass beds and led to large fish kills and abnormal mortalities of dolphin, manatees and shorebirds.

Brevard County’s approach to healing the lagoon is based on the four “R’s”, remove, reduce, restore and respond; remove accumulations of nutrient laden muck, reduce pollutants and nutrients entering the lagoon, restore water-filtering ecosystems and respond to changing conditions and evolving technologies. The county intends to focus on projects that offer the biggest bang for the buck; the highest levels of nutrient reduction per dollar spent.

Remove

Over 15,000 acres of the lagoon’s bottom is covered by muck, and almost two-thirds of the sales tax revenues will be used for muck removal. Muck, a black ooze that smells of rotting eggs, is the byproduct of years of excessive nutrient accumulation that collects in the deeper portions of the lagoon. It coats the bottom and inhibits the grown of seagrasses and benthic (bottom dwelling) organisms. When disturbed by waves, currents, boating activities or other factors, muck disperses into the water column and releases nutrients and pollutants that contribute to algal blooms and seagrass die-offs. Decaying muck releases almost as much nutrients into the IRL as stormwater and groundwater baseflow combined and therefore dredging muck deposits from the lagoon is a high priority for the restoration efforts.

Reduce

Muck removal doesn’t help much if we continue to dump silt and nutrients back into the lagoon. Primary sources of external nutrient loading for the IRL are excess fertilizer applications, stormwater runoff, septic systems, and wastewater treatment facility discharges.

We got a head start on the problem of excess fertilizer when Brevard County and its municipalities adopted fertilizer ordinances starting in 2012. The county began educational and outreach programs to inform residents about lagoon friendly fertilizers and proper application techniques. Funds from the sales tax will be used to expand public education campaigns and to work with stores to promote sales of ordinance compliant fertilizers.

Brevard County has over 1,500 stormwater outfalls into the IRL. Stormwater runoff transports nutrients, pesticides, oil, sediments and other debris into the lagoon. Local governments and the St. Johns Water Management District have been implementing stormwater management for years using techniques like detention ponds, swales, baffle boxes, managed aquatic plant systems and more. Sales tax funds will be used to enhance the nutrient removal efficiency of existing and new stormwater systems.

Waste water treatment facilities (WWTF) no longer discharge directly into the lagoon and treated effluent is mostly used for reclaimed water irrigation. The County applies about 18.5 million gallons of reclaimed water per day to over 7,340 acres of land. Although reclaimed water irrigation is an excellent way to conserve water, reclaimed water often contains high nutrient concentrations that can leach into groundwater and eventually the lagoon. It would not be cost effective to upgrade all WWTF’s in Brevard County compared to the efficiency of other lagoon restoration programs, however two facilities, one in Titusville and the other in Palm Bay, show favorable levels of nutrient reductions relative to the amount of upgrade dollars spent.

Perhaps the most troublesome source of nutrient loading for the IRL is nearly 59,500 septic systems within the IRL watershed that leach nutrients into groundwater that eventually migrate into the lagoon. It would cost over a billion dollars to convert all 59,500 septic tanks to central sewage treatment which is well above the funding from the ½ cent sales tax. Studies show septic systems within 55 yards of surface waters (the IRL, canals, creeks and ditches) have the most deleterious effect while systems more than 219 yards away from surface waters contribute very little nutrients into the lagoon. The County will focus efforts on septic systems close to surface waters, in locations with central sewer infrastructure already in place. In locations without adequate infrastructure, the County could implement a variety of upgrades to increase the nutrient removal efficiency of existing septic systems.

Restore

An important component to the IRL plan is to restore water filtering ecosystems. The County intends to plant approximately 20 miles of oyster reef along the shores of the IRL which is enough oysters to filter the entire volume of lagoon water annually. Besides cleaning the water and filtering nutrients, especially nitrogen, oyster reefs function as natural breakwaters that protect against shoreline erosion.

Respond

The final component of the IRL restoration plan involves dedicating a million dollars per year to monitor restoration projects to ensure they are providing acceptable levels of nutrient reductions for the monies spent. They will also evaluate new technologies and the plan can be modified as needed to employ more cost effective projects.

Our lagoon’s woes are due to decades of abuse so we can’t expect her to heal overnight. With the approval of the ½ cent sales tax referendum, Brevard County now has funds to aggressively pursue restoration efforts. The success of similar projects in places like the Chesapeake Bay and Tampa Bay should give us confidence the Indian River Lagoon can again be a healthy ecosystem with an abundance of the gamefish we so love to pursue. If you want to learn more about restoration efforts visit http://www.brevardfl.gov/SaveOurLagoon/Home.

By Paul MacInnis